23 Feb 2025

Volume 2

Views:1239

Downloads:7

Review Article | Open Access

The role of adipose tissue aging in organismal aging

Al Maskari Raya1, Nomier Yousra1

1Faculty and Building of Pharmacology and clinical Pharmacy, Sultan Qaboos University, Al-Khod District, Muscat Governorate, Sultanate of Oman.

Correspondence: Nomier Yousra (Faculty and Building of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, Sultan Qaboos University, Al-Khod District, Muscat Governorate, Sultanate of Oman; E-mail: y.nomeir@gmail.com).

Asia-Pacific Journal of Surgical & Experimental Pathology 2025, 2: 28-37. https://doi.org/10.32948/ajsep.2025.02.15

Received: 17 Jan 2025 | Accepted: 20 Feb 2025 | Published online: 23 Feb 2025

Abstract

Aging, a complex process marked by the progressive decline in cellular and systemic functions, increases vulnerability to metabolic and age-associated disorders. Adipose tissue, being the largest energy reservoir in the body, plays a crucial role in regulating metabolism and maintaining energy balance. Adipose tissue exhibit early onset of age-associated dysfunctions, which ultimately contribute to organismal aging. For instance, the secretion of adipokines and batokines from adipose tissue becomes dysregulated with aging, not only facilitating metabolic disturbances but also hindering proper communication between different tissue and organs by disrupting both paracrine and endocrine signaling mechanisms. This dysregulation leads to the decline in physiological function in remote organs and tissues such as the liver, heart, and skeletal muscles, thus promoting the onset of age-related pathologies, such as obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes and cardiovascular conditions, and accelerating organismal aging. The interconnection between adipose tissue aging and obesity, with both sharing molecular and physiological characteristics, such as increased oxidative stress, senescent cell accumulation, and chronic inflammation, amplify systemic metabolic dysfunctions and predispose to plethora of diseases. Moreover, pro-inflammatory cytokines, excessively produced in aging adipose tissue, worsens immune system dysfunction and fosters chronic inflammation throughout the body, aiding in disease onset and progression. Hence, in-depth understanding of the role of adipose tissue aging in organismal aging is instrumental, targeting which by lifestyle modulation and therapeutic interventions, such as calorie restriction, and pharmacological agents like metformin and senolytics, offer promising strategies to delay organismal aging, enhance metabolic health, and extend lifespan.

Key words adipose aging, systemic aging, adipokines, batokines, inflammation, calorie restriction, senolytics

Introduction

Aging, characterized by progressive decline in physiological function over time, leads to compromised cellular and organ function, reflecting the gradual breakdown of regenerative and protective processes in most living organisms [1]. Aging-related changes often increase susceptibility to major pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune conditions, and neurodegenerative disorders, ultimately heightening mortality risk [2, 3]. Although it is a continuous process, beginning at birth and continuing throughout life, onset of aging varies across tissues, and the rate of aging differs in a tissue-specific manner over time. Furthermore, cells and/or cell types within a tissue also often exhibit varying aging patterns [4]. Adipose tissue, the body’s largest energy reservoir and a key endocrine organ essential for maintaining metabolic balance [5], is among the first organ to undergo aging-related changes [6]. Adipose tissue plays a critical role in regulating various physiological functions, including appetite, glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and tissue repair [7, 8]. In addition, adipose tissue interacts with other organs by releasing endocrine factors called adipokines and batokines. Aging disrupts the regulation of these molecules, impairing the tissue's capacity to effectively manage nutrient excess, which increases the risk of obesity, a significant driver of accelerated aging [9]. Moreover, adipose tissue secretes inflammatory cytokines, and aging-related disturbances in its secretory profile contribute to chronic inflammation which is linked to a variety of age-associated disorders [10]. Gaining a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of adipose tissue aging is crucial for achieving the broader objective of identifying pharmacological interventions to target adipose tissue aging, and enhance human health by counteracting organismal aging. Such advancements could help combat aging-related challenges and metabolic disorders, including obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes. Here, we explore the role of adipose tissue aging in influencing organismal aging by discussing the impact of aging-related changes in adipokines and batokines secretion, the interplay between adipose tissue aging and obesity, and aging adipose tissue-driven inflammatory signaling on organismal aging. Furthermore, we present ongoing research efforts aimed at targeting adipose tissue therapeutically to promote healthy aging.

Adipose tissue aging: a trigger for organismal aging

Nearly all tissue types experience age-associated shifts in the expression of critical molecular pathways and biological processes, including extracellular matrix remodeling, the unfolded protein stress response, mitochondrial activity, immune cell infiltration, and inflammation. However, the timing and extent of these expression changes vary significantly between tissues, resulting in an asynchronous pattern of aging across different tissue types [11, 12]. Evidence from a comprehensive RNA-sequencing study, which analyzed 17 organs alongside plasma proteomics across 10 stages of the murine lifespan, reveals that aging-related changes in adipose tissue commence earlier than in other tissues. Given the central function of adipose tissue in maintaining energy homeostasis and its systemic interactions with other tissues and organs through its secreted factors, such as adipokines and batokines, this early onset may hasten the aging process throughout the organism by precipitating in physiological decline in other tissues [11]. Supporting this observation, a proteomic analysis targeting young and old murine tissues has highlighted that adipose tissue shows pronounced age-related disruptions in lipid metabolism, central carbon metabolism, electron transport chain activity, and inflammatory processes [12]. In addition, early aging in adipose tissue is also evident from the observation that scapular brown adipose tissue which is present during infancy, is gradually lost overtime [6]. White adipose tissue, in particular, is a major source of pro-aging plasma proteins, which may drive accelerated aging throughout the body [11, 13]. These early abnormalities in adipose tissue metabolism are linked to reduced fat storage capacity in mature adipocytes. This impairment exposes other tissues to harmful free fatty acids, which can lead to complications such as fat accumulation in the liver, exacerbating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease during aging and contributing to the overall aging process [14, 15]. Hence, early onset of adipose tissue aging serves trigger for organismal aging (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Adipose tissue aging. The distribution of fat mass undergoes significant changes with aging, characterized by reduced subcutaneous and brown fat, and an increased visceral fat, particularly in the lower body regions.

Aging adipose tissue-driven dysregulated adipokines drive organismal aging

Adipose tissue communicates with other tissues by releasing signaling molecules, such as adipokines (leptin, adiponectin, resistin etc) into circulation, which modulate metabolic and functional activities of target organs [16]. For instance, both leptin and adiponectin are vital in preventing β-cell dysfunction by shielding insulin-producing cells from apoptosis induced by cytokines and fatty acids, thereby indirectly supporting glucose regulation [17]. Circulating leptin levels are proportional to body fat mass and are sensed by the hypothalamus to regulate appetite by increasing anorexigenic peptides and decreasing orexigenic peptides, thereby maintaining energy balance [18]. However, with aging, structural and functional decline in white adipose tissue disrupts leptin signaling, leading to hypothalamic dysfunction and leptin resistance. This condition persists even in the presence of high circulating leptin levels, contributing to obesity [16]. Leptin plays a significant role in liver dysfunction as elevated leptin levels in the bloodstream are linked to the development of hepatic steatosis and cirrhosis and contribute to hepatic insulin resistance [19, 20]. In contrast, adiponectin, known for its insulin-sensitizing properties, is considered protective against metabolic syndrome. Decreased levels of adiponectin are often observed in metabolic conditions like obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. However, elevated plasma adiponectin concentrations are associated with diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, chronic heart failure, and chronic kidney disease [21]. Unlike these adipokines, resistin, primarily secreted by inflammatory cells within adipose tissue, is involved in various physiological processes, including glucose and lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation, angiogenesis, cardiac dysfunction, and bone remodeling [22]. Resistin derived from adipose tissue hinders insulin signaling while reducing glucose uptake in adipocytes and muscle cells. Additionally, resistin activates NF-kB signaling, promoting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, leading to vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, endothelial damage, and accelerated cardiovascular disease onset [23]. Adipose tissue also produces numerous other adipokines, such as vaspin, omentin and apelin, dysregulations in which are also implicated in organ dysfunction and related diseases [16]. Hence, adipokines from aging adipose tissue contribute to organismal aging (Figure 1).

Aging adipose tissue-driven dysregulated batokines drive organismal aging

Similar to white adipose tissue, a decline in brown adipose tissue function adversely impacts the metabolism of other organs, particularly the liver, heart, and skeletal muscles, by disrupting the secretion of brown adipose tissue-specific regulatory factors, called batokines [24]. Brown adipose tissue mitigates insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis by releasing neuregulin 4 (NRG4), an endocrine factor, which limits hepatic lipogenesis via activation of the ErbB signaling pathway in liver cells [25]. Additionally, the secretory profile of brown adipose tissue may offer protection to hepatocytes, shielding them from apoptosis triggered by lipotoxicity. Interestingly, alcohol consumption has been associated with increased brown adipose tissue activity, and specific batokines, including interleukin 6 (IL-6) and adiponectin, are implicated in mitigating liver injury and steatosis resulting from alcohol intake [26]. Additionally, the brown adipose tissue-specific upregulation of phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) enhances bile acid production in the liver, improves insulin sensitivity, and supports glucose uptake and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue [27]. While the secretion of IL-6 driven by brown adipose tissue enhances the thermogenic capacity of adipose tissue by promoting browning within white adipose tissue, IL-6 released from brown adipose tissue through β3AR signaling can exacerbate hyperglycemia by stimulating hepatic gluconeogenesis under acute physiological stress conditions [28]. During periods of hyperactivation, brown adipose tissue may become a major source of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) that regulates obesity, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance through autocrine and paracrine signaling in liver and adipose tissue. In addition, FGF21 may provide liver protection against steatosis and non-alcoholic liver disease [29, 30]. Furthermore, brown adipose tissue-derived microRNA-99b (miR-99b) influences liver metabolism by targeting FGF21 expression in the liver, highlighting brown adipose tissue’s crucial role in systemic FGF21 regulation [31]. The cardio-protective functions of brown adipose tissue are partly attributed to its release of factors such as FGF21 and 12,13-diHOME. Specifically, FGF21 from brown adipose tissue contributes to regulating cardiac remodeling and helps prevent hypertension [32], while 12,13-diHOME improves heart function by modulating calcium signaling pathways [33]. Epicardial adipose tissue, a brown adipose tissue-like adipose tissue located near the myocardium, release factors that promote myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis by upregulating miR-134-5p expression in cardiomyocytes, which subsequently increases reactive oxygen species production [34]. Brown adipose tissue and muscle perform complementary functions in thermogenesis, with muscle contributing to shivering thermogenesis and brown adipose tissue facilitating non-shivering heat production. This interplay ensures a balance between energy expenditure and heat generation during physical activity [35]. Brown adipose tissue activation enhances skeletal muscle development and functionality by secreting lower levels of myostatin compared to inactive brown adipose tissue, which produces higher myostatin levels associated with diminished exercise performance [36]. Brown adipose tissue also contributes to energy balance by releasing 12,13-diHOME, a paracrine factor that promotes fatty acid uptake and β-oxidation in skeletal muscle. However, aging reduces brown adipose tissue's release of 12,13-diHOME, which in turn limits energy expenditure during cold exposure and exercise [37]. Hence, batokines from aging adipose tissue are critical determining factors in organismal aging (Figure 1).

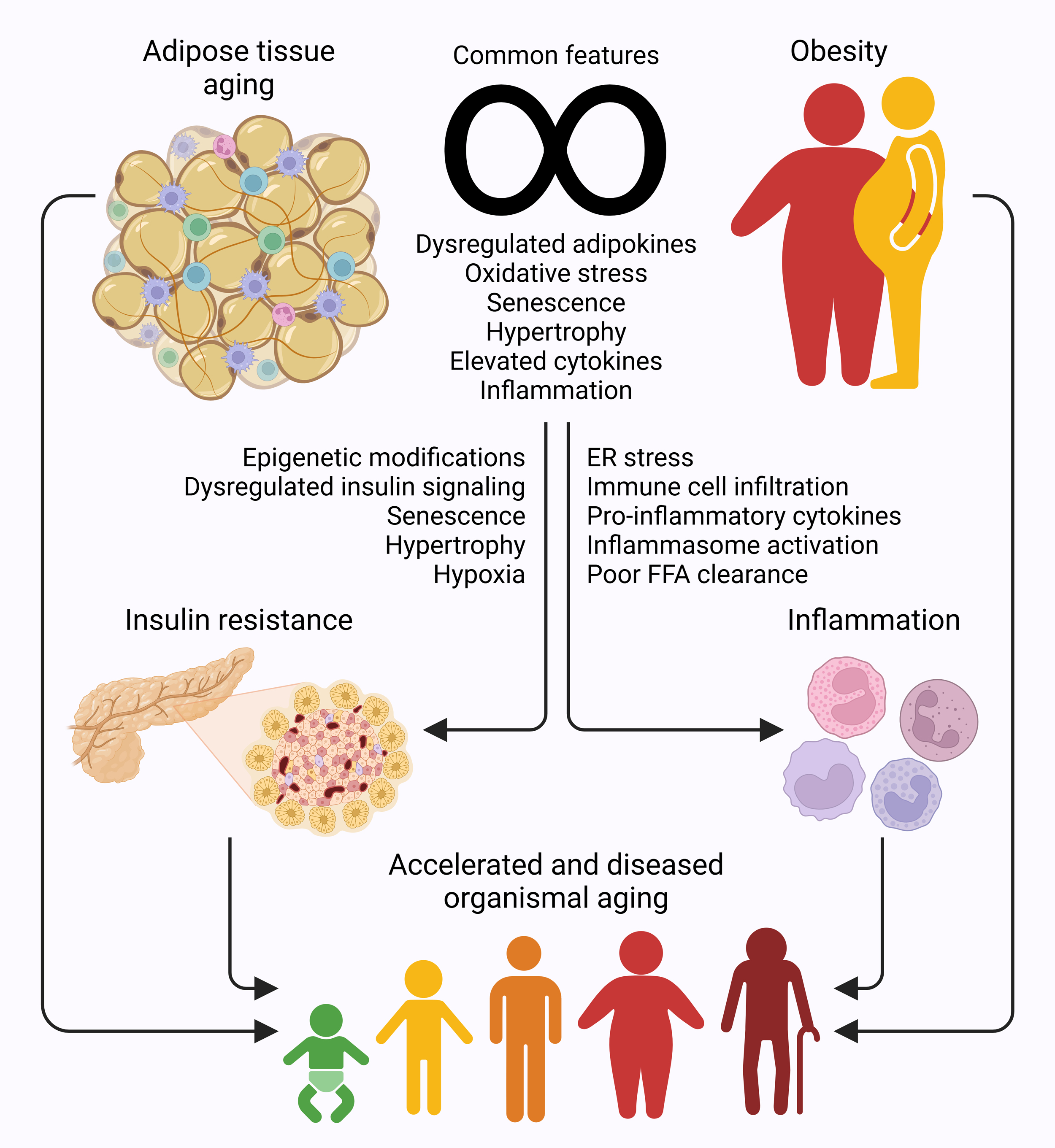

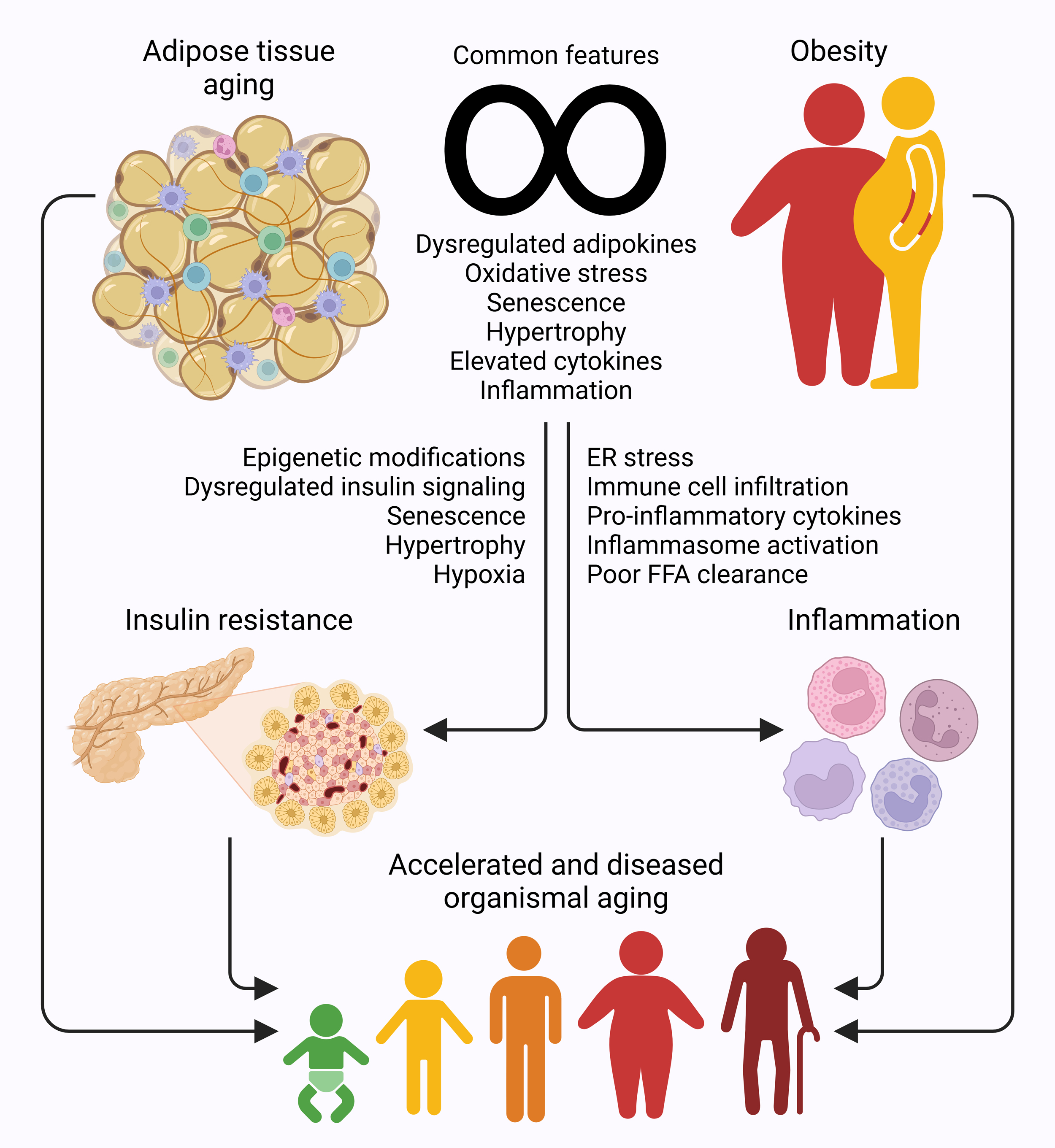

Aging adipose tissue-obesity link drives organismal aging

Obesity is weight gain due to a prolonged imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, resulting in accumulation of visceral fat. A positive energy balance prompts hypertrophy in adipocytes to address the imbalance, resulting in generation of new adipocytes from precursor cells to compensate for the excess nutrition, ultimately leading to obesity [38, 39]. Obesity shares notable similarities with adipose tissue aging at the molecular, morphological, and physiological levels. For instance, obese adipose tissue is marked by a heightened presence of senescent cells and low-grade inflammation, accompanied by increased oxidative stress, as well as elevated levels of adipokines and cytokines in the bloodstream [40, 41]. In addition, both aging and obesity contribute to a decline in brown adipose tissue mass and functionality. Individuals who are older or obese show a significant reduction in brown adipose tissue-specific uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression and decreased brown adipose tissue activity [42]. Furthermore, a significant reduction in telomere length in subcutaneous adipose tissue, as compared to visceral adipose tissue, is a key factor in the redistribution of fat that occurs with aging. Similarly, subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese individuals also shows shorter telomeres, which further links the obesity to aging process in adipose tissue [43]. Moreover, excessive hyperplastic growth following hypertrophic saturation in the visceral white adipose tissue during obesity plays a key role in the age-related redistribution of adipose tissue [44]. Obesity is strongly associated with the onset of systemic insulin resistance, where the body fails to respond appropriately to circulating insulin in key tissues like the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue, resulting in disrupted glucose metabolism [45, 46]. Obesity is also associated with the onset of other age-related conditions, such as diabetes, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular issues, arthritis, and cancer [47, 48]. The molecular processes that connect obesity to these metabolic disorders are primarily characterized by an imbalance in adipokine secretion and the chronic elevation of oxidative stress, which worsens with age [49]. In this line, three primary hypotheses have been proposed to explain how obesity negatively affects various tissues and organs, leading to diseases associated with accelerated aging. 1) Obesity-associated chronic inflammation, coupled with the release of inflammatory mediators from adipose tissue during obesity, causes pathological alterations in distant organs. 2) Obesity-related inability of adipose tissue to properly store fat results in ectopic fat accumulation in organs such as the liver, muscles, and pancreas. 3) Obesity triggers dysfunctional secretion of endocrine factors, such as adipokines and hormones, from white adipose tissue, which leads to metabolic disruptions in various target tissues and organs [50]. Notably, obesity is now linked to shorter lifespans in both animal models and human populations, as well as an elevated mortality rate in obese individuals [51]. Hence, interconnection between adipose tissue aging and obesity plays a critical role in organismal aging (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Aging adipose tissue-obesity link drives insulin resistance and inflammation in organismal aging. Adipose tissue shares molecular, morphological, and physiological similarities with obesity, with both contributing to onset of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, dysregulations that lead to metabolic and pathological conditions, and result in accelerated and diseased organismal aging.

Aging adipose tissue-driven insulin resistance drives organismal aging

Age-associated epigenetic modifications in adipose tissue are evident in genes linked to insulin signaling pathways, which subsequently contribute to the development of insulin resistance [52]. In addition, changes in the subcellular distribution of the insulin receptor and its substrate, IRS-1, as well as diminished insulin receptor activation in response to insulin happens with aging. Collectively, these alterations contribute to the development of insulin resistance in adipose tissue [53]. Cellular senescence, marked by increased adipocyte size, exacerbates metabolic dysfunction by activating p53 signaling pathways and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines [54]. Notably, inhibiting p53 activity has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue by mitigating senescence-like characteristics [55], as suppressing senescent adipose-derived stem/progenitor cells enhances their regenerative potential, adipogenic differentiation, and metabolic functions [56]. Elevated circulation of retinol-binding protein-4 (RBP4) in obese individuals impairs PI3K signaling in muscles and stimulates gluconeogenesis in the liver, ultimately promoting the development of insulin resistance [57]. While the hypertrophic enlargement of adipocytes with aging enhances lipid storage capacity, it simultaneously reduces the surface area-to-volume ratio, impairing nutrient transport and intracellular signaling in these cells. This aligns with findings that associate hypertrophic white adipose tissue with insulin resistance and diabetes in obese individuals [58]. Additionally, hypertrophic growth restricts vascular development and oxygen delivery while fostering inflammation [59]. Aging adipocytes may exhibit heightened oxygen consumption, which can initiate hypoxic signaling pathways that contribute to inflammation and insulin resistance [60]. Chronic hypoxia, accompanied by reduced vascularization and diminished expression of the angiogenic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), is a hallmark of aging adipose tissue and significantly contributes to its metabolic dysfunction [61]. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) plays a crucial role in the age-associated decline of mitochondrial activity in adipocytes by regulating the expression of various transcripts essential for mitochondrial complex VI assembly [62]. The interplay between hypertrophic growth and hypoxia also influences extracellular matrix remodeling, primarily through increased collagen deposition, which can lead to tissue fibrosis [63]. Lower expression of periostin, a non-structural extracellular matrix component, in aged adipose tissue has been linked to reduced β-adrenergic responsiveness and impaired lipid utilization [64]. If left unchecked, insulin resistance can progress to metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that may include diabetes, hypertension, liver and kidney diseases, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular problems [45]. Modulating hypoxia signaling pathways has shown promise in reducing adipocyte size in middle-aged mice [62] and mitigating insulin resistance in obese mice [65]. Hence, adipose tissue-driven insulin resistance fosters organismal aging (Figure 2).

Aging adipose tissue-driven inflammation drives organismal aging

Adipose tissue is susceptible to age-related inflammation, with significant immune cell activation becoming evident in white adipose tissue as early as middle age [11, 12]. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, which becomes more pronounced with aging, disrupts the normal function of adipose tissue. Heightened ER stress responses in adipose tissue lead to an increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby contributing to organismal aging [66]. The infiltration of immune cells and the presence of chronic inflammation within aging adipose tissue are key contributors to metabolic dysfunction [67]. Increased macrophage infiltration during aging is accompanied by heightened activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and worsens insulin resistance in adipose tissue [68]. NLRP3 inflammasome in aging adipose tissue collaborates with activated T cells within the microenvironment, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, intensifying inflammation in both adipose tissue and the liver, ultimately leading to insulin resistance [68]. Excessive secretion of IL-1 family cytokines within adipose tissue disrupts insulin signaling pathways, thereby aggravating insulin resistance [69]. The interplay between IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) synergistically enhances IL-6 expression during states of obesity and insulin resistance by facilitating CREB binding to the IL-6 promoter [70]. Approximately 30% of circulating pro-inflammatory IL-6 during age-associated systemic inflammation is secreted by white adipose tissue [71]. This situation is further exacerbated by age-related redistribution of adipose tissue, as visceral adipose tissue produces higher levels of IL-6 compared to subcutaneous adipose tissue [72]. Hypertrophic adipocytes are characterized by increased production of pro-inflammatory mediators, including leptin, IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), alongside a diminished secretion of anti-inflammatory agents such as adiponectin and IL-10 [16] This imbalance contributes significantly to adipose tissue dysfunction. Additionally, elevated levels of circulating TNF-α further accelerate organismal aging by impairing hematopoietic stem cell functionality, driving these cells toward a myeloid lineage bias by inducing the expression of IL-27 receptor alpha (IL-27Ra) through the ERK-ETS1 signaling pathway in hematopoietic stem cells [73]. Furthermore, aging adipose tissue demonstrates reduced efficiency in clearing free fatty acids, resulting in an increased release of lipids and fatty acids into the bloodstream, which may further aggravate systemic inflammation. For instance, the presence of excessive non-esterified fatty acids in circulation has been shown to enhance CD11b expression in monocytes, facilitating their adhesion to endothelial cells and contributing to the development of atherosclerosis [74]. Notably, the process of immune cell infiltration, crucial for clearing senescent cells, is often delayed in other organs due to the age-associated accumulation of these cells in adipose tissue. This delay allows senescent cells to act as reservoirs of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are released as part of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, thereby sustaining systemic inflammation over time [75]. Interestingly, thermogenic activation of brown adipose tissue stimulates the release of C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 4 (CXCL14) and growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF15), which may collectively reduce inflammation and metabolic dysfunction by modulating macrophage infiltration and suppressing the pro-inflammatory activity of macrophages [76, 77]. Hence, adipose tissue-driven inflammation accelerates organismal aging (Figure 2).

Targeting adipose tissue aging to counteract organismal aging

Calorie restriction prevents the accumulation of fat associated with aging and mitigates its harmful impact on nearby tissues and distant organs. On a molecular level, calorie restriction rejuvenates adipose tissue function by restoring the white adipose tissue-specific expression of PPAR-γ, a key regulator of adipogenesis and lipid metabolism, in older animals [78]. Sirtuins (SIRTs) are essential enzymes that play a pivotal role in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Both calorie restriction and the SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of PPAR-γ have been independently linked to reduced fat accumulation through the induction of browning in white adipose tissue [79, 80]. SIRTs require specific cofactors, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and Zinc, to perform their functions. However, with advancing age, the expression of SIRTs and the availability of NAD+ and Zn decline across the body, impairing their proper functioning [81, 82]. For instance, SIRT7 expression decreases in subcutaneous adipose tissue with age [83]. SIRT7 regulates adipose tissue homeostasis and fat accumulation by promoting PPAR-γ-driven lipogenesis and by indirectly inhibiting SIRT1 activity [84]. Certain dietary components, such as biotin, act as negative regulators of SIRT1 activity. Notably, calorie restriction lowers biotin levels, which helps limit fat accumulation and stimulates lipolysis by enhancing SIRT1 activity in adipose tissue [85]. Calorie restriction can also restore the healthy activity of SIRTs, either by directly increasing SIRT expression or indirectly by boosting NAD+ levels [79, 80]. Calorie restriction may also promote health and lifespan extension by triggering AMP-activated protein kinase signaling, which stimulates autophagy [86]. Furthermore, calorie restriction is considered to be five times more effective in extending lifespan than the surgical removal of visceral adipose tissue [87]. A recent study has revealed that adipose tissue retains an epigenetic memory of fat accumulation and obesity even after weight loss [88], reinforcing the need for sustained healthy lifestyles and dietary practices to prevent harmful fat accumulation and enhance healthspan during aging.

At the therapeutic front, senolytic therapies have garnered significant attention as potential anti-aging treatments. A senolytic cocktail, D+Q, has been shown to reduce physical dysfunction in older individuals by eliminating senescent cells and decreasing the pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype released from adipose tissue, thus enhancing survival in animal models during late life [89]. Furthermore, research demonstrates that a specific senolytic treatment, utilizing a targeted cocktail, effectively removes senescent cells expressing p16 and p21, particularly in adipose tissues. This intervention helps combat aging by reducing circulating levels of pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-1α, IL-6, and MMPs, in subjects with diabetic kidney disease [90]. Metformin, an anti-diabetic and anti-aging drug, mimics the effects of calorie restriction and improves fatty acid metabolism by modulating adipogenic signaling, mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and extracellular matrix remodeling [91]. Moreover, metformin increases the expression of FGF21, which helps reduce the accumulation of white adipocytes and promotes browning in white adipose tissue [92]. Additionally, the PPAR-γ agonist, rosiglitazone, has been shown to prolong the lifespan of animals. This effect is attributed to the drug’s ability to enhance insulin sensitivity, preserve adipose tissue integrity, and counteract mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, fibrosis, and tissue degeneration. It also helps mitigate symptoms related to anxiety and depression [93]. An increase in the expression of nuclear receptor-interaction protein 1 (NRIP1) is believed to be linked to the expansion of visceral adipose tissue with age. Targeting NRIP1 in animal models has been shown to extend lifespan by enhancing autophagy and reducing cellular senescence and inflammation in white adipose tissue [94]. Heterochronic parabiosis, which involves linking the circulatory systems of young and older animals, alleviates signs of cellular senescence in the visceral adipose tissue of the aged by downregulating the expression of p16 and p21, while also lowering levels of inflammatory molecules in circulation [95]. Despite these promising findings, the clinical application of above-discussed therapies remains obscure, highlighting the urgent need for more research to develop therapeutic strategies to target adipose tissue aging in a hope to alleviate organismal aging.

Conclusion

Aging adipose tissue fosters organismal aging due to its multifaceted roles in metabolic regulation, energy storage, and endocrine signaling. Adipose tissue influences systemic health through its dynamic interactions with other tissues via adipokines, batokines, and inflammatory mediators. Aging-related structural and functional impairments in adipose tissue, such as altered adipokine profiles and chronic inflammation, disrupt metabolic equilibrium and contribute to the onset of age-associated disorders, like obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases. Notably, obesity exacerbates these effects by amplifying adipose tissue dysfunction, fostering a state of persistent oxidative stress and inflammation. Current therapeutic approaches, including calorie restriction, and pharmacological agents like metformin, and senolytic therapies, have shown promise in mitigating the detrimental effects of adipose tissue aging. These interventions target pathways, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance, while promoting beneficial processes like autophagy and mitochondrial function. Moreover, strategies aimed at enhancing brown adipose tissue activity hold potential for improving systemic metabolism and energy expenditure. However, clinical translation of these preclinical findings related to targeting adipose tissue is far from reach. The heterogeneity of aging across different adipose depots and individual variability in response to therapies underscore the need for personalized approaches in managing adipose tissue aging. Future research on unraveling the precise molecular mechanisms driving adipose tissue aging and its impact on organismal aging, with an emphasis on developing targeted interventions, will help in addressing the metabolic challenges associated with aging, and pave the way for innovative strategies to enhance healthspan and lifespan in aging populations.

Declaration

Acknowledgments

No applicable.

Ethics approval

No applicable.

Data availability

The data will be available upon request.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contribution

Al Maskari Raya contributed to the design and writing of this review article. Nomier Yousra cellected data and drew figures for the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

-

Flint B, Tadi P: Physiology, Aging. In: StatPearls. Epub ahead of print., edn. Treasure Island (FL), 2021.

-

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G: The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153(6): 1194-1217.

-

Moskalev AA, Shaposhnikov MV, Plyusnina EN, Zhavoronkov A, Budovsky A, Yanai H, Fraifeld VE: The role of DNA damage and repair in aging through the prism of Koch-like criteria. Ageing Res Rev 2013, 12(2): 661-684.

-

Rando TA, Wyss-Coray T: Asynchronous, contagious and digital aging. Nat Aging 2021, 1(1): 29-35.

-

Nguyen TT, Corvera S: Adipose tissue as a linchpin of organismal ageing. Nat Metab 2024, 6(5): 793-807.

-

Graja A, Gohlke S, Schulz TJ: Aging of Brown and Beige/Brite Adipose Tissue. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2019, 251: 55-72.

-

Scheja L, Heeren J: The endocrine function of adipose tissues in health and cardiometabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019, 15(9): 507-524.

-

Fukuoh T, Nozaki Y, Mizunoe Y, Higami Y: Regulation of Aging and Lifespan by White Adipose Tissue. Yakugaku Zasshi 2024, 144(4): 411-417.

-

Folch J, Pedrós I, Patraca I, Martínez N, Sureda F, Camins A: Metabolic basis of sporadic Alzeimer's disease. role of hormones related to energy metabolism. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19(38): 6739-6748.

-

Santos AL, Sinha S: Obesity and aging: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 67: 101268.

-

Schaum N, Lehallier B, Hahn O, Pálovics R, Hosseinzadeh S, Lee SE, Sit R, Lee DP, Losada PM, Zardeneta ME, et al: Ageing hallmarks exhibit organ-specific temporal signatures. Nature 2020, 583(7817): 596-602.

-

Yu Q, Xiao H, Jedrychowski MP, Schweppe DK, Navarrete-Perea J, Knott J, Rogers J, Chouchani ET, Gygi SP: Sample multiplexing for targeted pathway proteomics in aging mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117(18): 9723-9732.

-

Brigger D, Riether C, van Brummelen R, Mosher KI, Shiu A, Ding Z, Zbären N, Gasser P, Guntern P, Yousef H, et al: Eosinophils regulate adipose tissue inflammation and sustain physical and immunological fitness in old age. Nat Metab 2020, 2(8): 688-702.

-

Koehler EM, Schouten JN, Hansen BE, van Rooij FJ, Hofman A, Stricker BH, Janssen HL: Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam study. J Hepatol 2012, 57(6): 1305-1311.

-

Guo W, Pirtskhalava T, Tchkonia T, Xie W, Thomou T, Han J, Wang T, Wong S, Cartwright A, Hegardt FG, et al: Aging results in paradoxical susceptibility of fat cell progenitors to lipotoxicity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007, 292(4): E1041-1051.

-

Fasshauer M, Blüher M: Adipokines in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36(7): 461-470.

-

Lee YH, Magkos F, Mantzoros CS, Kang ES: Effects of leptin and adiponectin on pancreatic β-cell function. Metabolism 2011, 60(12): 1664-1672.

-

Mantzoros CS, Magkos F, Brinkoetter M, Sienkiewicz E, Dardeno TA, Kim SY, Hamnvik OP, Koniaris A: Leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011, 301(4): E567-584.

-

Chitturi S, Farrell G, Frost L, Kriketos A, Lin R, Fung C, Liddle C, Samarasinghe D, George J: Serum leptin in NASH correlates with hepatic steatosis but not fibrosis: a manifestation of lipotoxicity? Hepatology 2002, 36(2): 403-409.

-

McCullough AJ, Bugianesi E, Marchesini G, Kalhan SC: Gender-dependent alterations in serum leptin in alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1998, 115(4): 947-953.

-

Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T: Adiponectin receptor as a key player in healthy longevity and obesity-related diseases. Cell Metab 2013, 17(2): 185-196.

-

Acquarone E, Monacelli F, Borghi R, Nencioni A, Odetti P: Resistin: A reappraisal. Mech Ageing Dev 2019, 178: 46-63.

-

Chen C, Jiang J, Lü JM, Chai H, Wang X, Lin PH, Yao Q: Resistin decreases expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase through oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010, 299(1): H193-201.

-

Gavaldà-Navarro A, Villarroya J, Cereijo R, Giralt M, Villarroya F: The endocrine role of brown adipose tissue: An update on actors and actions. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 23(1): 31-41.

-

Wang GX, Zhao XY, Meng ZX, Kern M, Dietrich A, Chen Z, Cozacov Z, Zhou D, Okunade AL, Su X, et al: The brown fat-enriched secreted factor Nrg4 preserves metabolic homeostasis through attenuation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nat Med 2014, 20(12): 1436-1443.

-

Shen H, Jiang L, Lin JD, Omary MB, Rui L: Brown fat activation mitigates alcohol-induced liver steatosis and injury in mice. J Clin Invest 2019, 129(6): 2305-2317.

-

Sponton CH, Hosono T, Taura J, Jedrychowski MP, Yoneshiro T, Wang Q, Takahashi M, Matsui Y, Ikeda K, Oguri Y, et al: The regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis via PLTP as a mediator of BAT-liver communication. EMBO Rep 2020, 21(9): e49828.

-

Qing H, Desrouleaux R, Israni-Winger K, Mineur YS, Fogelman N, Zhang C, Rashed S, Palm NW, Sinha R, Picciotto MR, et al: Origin and Function of Stress-Induced IL-6 in Murine Models. Cell 2020, 182(6): 1660.

-

Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ: A Dozen Years of Discovery: Insights into the Physiology and Pharmacology of FGF21. Cell Metab 2019, 29(2): 246-253.

-

Markan KR, Naber MC, Ameka MK, Anderegg MD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA, Mohammadi M, Potthoff MJ: Circulating FGF21 is liver derived and enhances glucose uptake during refeeding and overfeeding. Diabetes 2014, 63(12): 4057-4063.

-

Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, et al: Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature 2017, 542(7642): 450-455.

-

Ruan CC, Kong LR, Chen XH, Ma Y, Pan XX, Zhang ZB, Gao PJ: A(2A) Receptor Activation Attenuates Hypertensive Cardiac Remodeling via Promoting Brown Adipose Tissue-Derived FGF21. Cell Metab 2020, 32(4): 689.

-

Pinckard KM, Shettigar VK, Wright KR, Abay E, Baer LA, Vidal P, Dewal RS, Das D, Duarte-Sanmiguel S, Hernández-Saavedra D, et al: A Novel Endocrine Role for the BAT-Released Lipokine 12,13-diHOME to Mediate Cardiac Function. Circulation 2021, 143(2): 145-159.

-

Hao S, Sui X, Wang J, Zhang J, Pei Y, Guo L, Liang Z: Secretory products from epicardial adipose tissue induce adverse myocardial remodeling after myocardial infarction by promoting reactive oxygen species accumulation. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12(9): 848.

-

Nirengi S, Stanford K: Brown adipose tissue and aging: A potential role for exercise. Exp Gerontol 2023, 178: 112218.

-

Kong X, Yao T, Zhou P, Kazak L, Tenen D, Lyubetskaya A, Dawes BA, Tsai L, Kahn BB, Spiegelman BM, et al: Brown Adipose Tissue Controls Skeletal Muscle Function via the Secretion of Myostatin. Cell Metab 2018, 28(4): 631-643.e633.

-

Stanford KI, Lynes MD, Takahashi H, Baer LA, Arts PJ, May FJ, Lehnig AC, Middelbeek RJW, Richard JJ, So K, et al: 12,13-diHOME: An Exercise-Induced Lipokine that Increases Skeletal Muscle Fatty Acid Uptake. Cell Metab 2018, 27(6): 1357.

-

Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, Bernard S, Buchholz BA, Bergmann O, Blomqvist L, Hoffstedt J, Näslund E, Britton T, et al: Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature 2008, 453(7196): 783-787.

-

Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, Beguinot F, Miele C: Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(9): 2358.

-

Minamino T, Orimo M, Shimizu I, Kunieda T, Yokoyama M, Ito T, Nojima A, Nabetani A, Oike Y, Matsubara H, et al: A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nat Med 2009, 15(9): 1082-1087.

-

Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I: Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2004, 114(12): 1752-1761.

-

Timmons JA, Pedersen BK: The importance of brown adipose tissue. N Engl J Med 2009, 361(4): 415-416.

-

Valdes AM, Andrew T, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Oelsner E, Cherkas LF, Aviv A, Spector TD: Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet 2005, 366(9486): 662-664.

-

Jeffery E, Wing A, Holtrup B, Sebo Z, Kaplan JL, Saavedra-Peña R, Church CD, Colman L, Berry R, Rodeheffer MS: The Adipose Tissue Microenvironment Regulates Depot-Specific Adipogenesis in Obesity. Cell Metab 2016, 24(1): 142-150.

-

Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP: Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008, 9(5): 367-377.

-

Ogawa W: Insulin resistance and adipose tissue. Diabetol Int 2023, 14(2): 117-118.

-

Blüher M: Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019, 15(5): 288-298.

-

Zhao Y, Yue R: Aging adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Biogerontology 2024, 25(1): 53-69.

-

Marseglia L, Manti S, D'Angelo G, Nicotera A, Parisi E, Di Rosa G, Gitto E, Arrigo T: Oxidative stress in obesity: a critical component in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 16(1): 378-400.

-

Chadt A, Scherneck S, Joost HG, Al-Hasani H: Molecular links between Obesity and Diabetes: “Diabesity”. In: Endotext. Epub ahead of print., edn. Edited by Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, et al. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000-2025, MDText.com, Inc., 2000.

-

Santos AL, Sinha S: Obesity and aging: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 67: 101268.

-

Małodobra-Mazur M, Cierzniak A, Myszczyszyn A, Kaliszewski K, Dobosz T: Histone modifications influence the insulin-signaling genes and are related to insulin resistance in human adipocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2021, 137: 106031.

-

Serrano R, Villar M, Gallardo N, Carrascosa JM, Martinez C, Andrés A: The effect of aging on insulin signalling pathway is tissue dependent: central role of adipose tissue in the insulin resistance of aging. Mech Ageing Dev 2009, 130(3): 189-197.

-

Nerstedt A, Smith U: The impact of cellular senescence in human adipose tissue. J Cell Commun Signal 2023, 17(3): 563-573.

-

Minamino T, Orimo M, Shimizu I, Kunieda T, Yokoyama M, Ito T, Nojima A, Nabetani A, Oike Y, Matsubara H, et al: A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nat Med 2009, 15(9): 1082-1087.

-

Xu M, Palmer AK, Ding H, Weivoda MM, Pirtskhalava T, White TA, Sepe A, Johnson KO, Stout MB, Giorgadze N, et al: Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. Elife 2015, 4: e12997.

-

Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N, Preitner F, Peroni OD, Zabolotny JM, Kotani K, Quadro L, Kahn BB: Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2005, 436(7049): 356-362.

-

Muir LA, Neeley CK, Meyer KA, Baker NA, Brosius AM, Washabaugh AR, Varban OA, Finks JF, Zamarron BF, Flesher CG, et al: Adipose tissue fibrosis, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia: Correlations with diabetes in human obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016, 24(3): 597-605.

-

Crewe C, An YA, Scherer PE: The ominous triad of adipose tissue dysfunction: inflammation, fibrosis, and impaired angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 2017, 127(1): 74-82.

-

Lee YS, Kim JW, Osborne O, Oh DY, Sasik R, Schenk S, Chen A, Chung H, Murphy A, Watkins SM, et al: Increased adipocyte O2 consumption triggers HIF-1α, causing inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Cell 2014, 157(6): 1339-1352.

-

Halberg N, Khan T, Trujillo ME, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Attie AD, Sherwani S, Wang ZV, Landskroner-Eiger S, Dineen S, Magalang UJ, et al: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29(16): 4467-4483.

-

Soro-Arnaiz I, Li QOY, Torres-Capelli M, Meléndez-Rodríguez F, Veiga S, Veys K, Sebastian D, Elorza A, Tello D, Hernansanz-Agustín P, et al: Role of Mitochondrial Complex IV in Age-Dependent Obesity. Cell Rep 2016, 16(11): 2991-3002.

-

Khan T, Muise ES, Iyengar P, Wang ZV, Chandalia M, Abate N, Zhang BB, Bonaldo P, Chua S, Scherer PE: Metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue fibrosis: role of collagen VI. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29(6): 1575-1591.

-

Graja A, Garcia-Carrizo F, Jank AM, Gohlke S, Ambrosi TH, Jonas W, Ussar S, Kern M, Schürmann A, Aleksandrova K, et al: Loss of periostin occurs in aging adipose tissue of mice and its genetic ablation impairs adipose tissue lipid metabolism. Aging Cell 2018, 17(5): e12810.

-

Jiang C, Qu A, Matsubara T, Chanturiya T, Jou W, Gavrilova O, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ: Disruption of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in adipocytes improves insulin sensitivity and decreases adiposity in high-fat diet-fed mice. Diabetes 2011, 60(10): 2484-2495.

-

Ghosh AK, Garg SK, Mau T, O'Brien M, Liu J, Yung R: Elevated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response Contributes to Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015, 70(11): 1320-1329.

-

Zhang YX, Ou MY, Yang ZH, Sun Y, Li QF, Zhou SB: Adipose tissue aging is regulated by an altered immune system. Front Immunol 2023, 14: 1125395.

-

Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD: The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med 2011, 17(2): 179-188.

-

Ballak DB, Stienstra R, Tack CJ, Dinarello CA, van Diepen JA: IL-1 family members in the pathogenesis and treatment of metabolic disease: Focus on adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Cytokine 2015, 75(2): 280-290.

-

Al-Roub A, Al Madhoun A, Akhter N, Thomas R, Miranda L, Jacob T, Al-Ozairi E, Al-Mulla F, Sindhu S, Ahmad R: IL-1β and TNFα Cooperativity in Regulating IL-6 Expression in Adipocytes Depends on CREB Binding and H3K14 Acetylation. Cells 2021, 10(11): 3228.

-

Starr ME, Evers BM, Saito H: Age-associated increase in cytokine production during systemic inflammation: adipose tissue as a major source of IL-6. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009, 64(7): 723-730.

-

72 Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS: Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998, 83(3): 847-850.

-

He H, Xu P, Zhang X, Liao M, Dong Q, Cong T, Tang B, Yang X, Ye M, Chang Y, et al: Aging-induced IL27Ra signaling impairs hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 2020, 136(2): 183-198.

-

Zhang WY, Schwartz E, Wang Y, Attrep J, Li Z, Reaven P: Elevated concentrations of nonesterified fatty acids increase monocyte expression of CD11b and adhesion to endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006, 26(3): 514-519.

-

Tchkonia T, Morbeck DE, Von Zglinicki T, Van Deursen J, Lustgarten J, Scrable H, Khosla S, Jensen MD, Kirkland JL: Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell 2010, 9(5): 667-684.

-

Campderrós L, Moure R, Cairó M, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Quesada-López T, Cereijo R, Giralt M, Villarroya J, Villarroya F: Brown Adipocytes Secrete GDF15 in Response to Thermogenic Activation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27(10): 1606-1616.

-

Cereijo R, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Cairó M, Quesada-López T, Villarroya J, Morón-Ros S, Sánchez-Infantes D, Peyrou M, Iglesias R, Mampel T, et al: CXCL14, a Brown Adipokine that Mediates Brown-Fat-to-Macrophage Communication in Thermogenic Adaptation. Cell Metab 2018, 28(5): 750-763.e6.

-

Linford NJ, Beyer RP, Gollahon K, Krajcik RA, Malloy VL, Demas V, Burmer GC, Rabinovitch PS: Transcriptional response to aging and caloric restriction in heart and adipose tissue. Aging Cell 2007, 6(5): 673-688.

-

Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, Zhao W, Lee S, Zhang Y, Rosenbaum M, Zhao Y, Gu W, Farmer SR, et al: Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell 2012, 150(3): 620-632.

-

Corrales P, Vivas Y, Izquierdo-Lahuerta A, Horrillo D, Seoane-Collazo P, Velasco I, Torres L, Lopez Y, Martínez C, López M, et al: Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates deleterious effects of aging on white and brown adipose tissue plasticity. Aging Cell 2019, 18(3): e12948.

-

Chini CCS, Tarragó MG, Chini EN: NAD and the aging process: Role in life, death and everything in between. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017, 455: 62-74.

-

de Oliveira Neto L, Tavares VDO, Agrícola PMD, de Oliveira LP, Sales MC, de Sena-Evangelista KCM, Gomes IC, Galvão-Coelho NL, Pedrosa LFC, Lima KC: Factors associated with inflamm-aging in institutionalized older people. Sci Rep 2021, 11(1): 18333.

-

Wronska A, Lawniczak A, Wierzbicki PM, Kmiec Z: Age-Related Changes in Sirtuin 7 Expression in Calorie-Restricted and Refed Rats. Gerontology 2016, 62(3): 304-310.

-

Akter F, Tsuyama T, Yoshizawa T, Sobuz SU, Yamagata K: SIRT7 regulates lipogenesis in adipocytes through deacetylation of PPARγ2. J Diabetes Investig 2021, 12(10): 1765-1774.

-

Xu C, Cai Y, Fan P, Bai B, Chen J, Deng HB, Che CM, Xu A, Vanhoutte PM, Wang Y: Calorie Restriction Prevents Metabolic Aging Caused by Abnormal SIRT1 Function in Adipose Tissues. Diabetes 2015, 64(5): 1576-1590.

-

Cantó C, Auwerx J: Calorie restriction: is AMPK a key sensor and effector? Physiology (Bethesda) 2011, 26(4): 214-224.

-

Muzumdar R, Allison DB, Huffman DM, Ma X, Atzmon G, Einstein FH, Fishman S, Poduval AD, McVei T, Keith SW, et al: Visceral adipose tissue modulates mammalian longevity. Aging Cell 2008, 7(3): 438-440.

-

Hinte LC, Castellano-Castillo D, Ghosh A, Melrose K, Gasser E, Noé F, Massier L, Dong H, Sun W, Hoffmann A, et al: Adipose tissue retains an epigenetic memory of obesity after weight loss. Nature 2024, 636(8042): 457-465.

-

Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK, Weivoda MM, Inman CL, Ogrodnik MB, Hachfeld CM, Fraser DG, et al: Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med 2018, 24(8): 1246-1256.

-

Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, Evans TK, Giorgadze N, Hashmi SK, Herrmann SM, Jensen MD, Jia Q, Jordan KL, et al: Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2019, 47: 446-456.

-

Kulkarni AS, Brutsaert EF, Anghel V, Zhang K, Bloomgarden N, Pollak M, Mar JC, Hawkins M, Crandall JP, Barzilai N: Metformin regulates metabolic and nonmetabolic pathways in skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissues of older adults. Aging Cell 2018, 17(2): e12723.

-

Kim EK, Lee SH, Jhun JY, Byun JK, Jeong JH, Lee SY, Kim JK, Choi JY, Cho ML: Metformin Prevents Fatty Liver and Improves Balance of White/Brown Adipose in an Obesity Mouse Model by Inducing FGF21. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016: 5813030.

-

Xu L, Ma X, Verma N, Perie L, Pendse J, Shamloo S, Marie Josephson A, Wang D, Qiu J, Guo M, et al: PPARγ agonists delay age-associated metabolic disease and extend longevity. Aging Cell 2020, 19(11): e13267.

-

Wang J, Chen X, Osland J, Gerber SJ, Luan C, Delfino K, Goodwin L, Yuan R: Deletion of Nrip1 Extends Female Mice Longevity, Increases Autophagy, and Delays Cell Senescence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018, 73(7): 882-892.

-

Ghosh AK, O'Brien M, Mau T, Qi N, Yung R: Adipose Tissue Senescence and Inflammation in Aging is Reversed by the Young Milieu. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019, 74(11): 1709-1715.

Cite this article: Raya AM, Yousra N: The role of adipose tissue aging in organismal aging. Asia Pac J Surg Exp & Pathol 2025, 2: 28-37. https://doi.org/10.32948/ajsep.2025.02.15

Figure 1. Adipose tissue aging. The distribution of fat mass undergoes significant changes with aging, characterized by reduced subcutaneous and brown fat, and an increased visceral fat, particularly in the lower body regions.

Figure 1. Adipose tissue aging. The distribution of fat mass undergoes significant changes with aging, characterized by reduced subcutaneous and brown fat, and an increased visceral fat, particularly in the lower body regions.

Figure 2. Aging adipose tissue-obesity link drives insulin resistance and inflammation in organismal aging. Adipose tissue shares molecular, morphological, and physiological similarities with obesity, with both contributing to onset of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, dysregulations that lead to metabolic and pathological conditions, and result in accelerated and diseased organismal aging.

Figure 2. Aging adipose tissue-obesity link drives insulin resistance and inflammation in organismal aging. Adipose tissue shares molecular, morphological, and physiological similarities with obesity, with both contributing to onset of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, dysregulations that lead to metabolic and pathological conditions, and result in accelerated and diseased organismal aging.

Copyright © Asia Pac J Surg Exp & Pathol. This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

License.

Copyright © Asia Pac J Surg Exp & Pathol. This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript