Review Article | Open Access

Healing through movement: narrative review on exercise and neurological disorders

Syed Muhammad Essa1, Amanullah Kakar1, Noor Ahmed Khosa1, Ismaiel A. Ibrahim2, Milica Jovanovic3, Maria Louise Mclaughlin4, Muhammad Ibrahim1, Karolina Riddle5

1Department of Neurology, Bolan Medical Complex Hospital, Brewery Road, Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan.

2Faculty of Health Sciences, Fenerbahçe University, Istanbul, Türkiye.

3University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia.

4Scholer Institute of Psychology, Psychiatry and Neurosciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom.

5Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu – National-Louis University, Nowy Sącz, Poland.

Correspondence: Syed Muhammad Essa (Department of Neurology, Bolan Medical Complex Hospital, Brewery Road, Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan; E-mail: dressakhan777@gmail.com).

Asia-Pacific Journal of Surgical & Experimental Pathology 2025, 2: 73-84. https://doi.org/10.32948/ajsep.2025.10.28

Received: 25 Sep 2025 | Accepted: 18 Dec 2025 | Published online: 22 Dec 2025

Methodology We reviewed PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar according to PRISMA criteria. The inclusion criteria included studies with peer review providing molecular insights into the effects of exercise on brain function.

Results Through neurotrophic factors, neurotransmitter modulation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and neuroprotection, exercise benefits brain function. These modifications are correlated with better mood management, enhanced cognitive function, and the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases.

Conclusion The various benefits of exercise on neurological disorders and brain health are highlighted in this study, with particular attention to key molecular pathways. Exercise is a vital tool in the management of neurological health.

Key words exercise, neuroprotection, prisma guidelines, neuro modulation, synaptic plasticity

The goal of this study is to present an overview of the current state of knowledge about the molecular mechanisms that explain exercise's positive effects on neurological diseases and brain function. Firstly, we will recap the benefits of physical activity for brain health and its possible effects on neurological conditions. After that, we will review a few of the molecular mechanisms that have been connected to mediating the impact of physical activity on the brain. To be more precise, we will discuss how exercise-induced modifications in brain function are influenced by substances such as neurotrophins, growth factors, and inflammatory cytokines.

Exercise may have a positive impact on neuroplasticity, the brain's capacity to adjust and change in response to experience [12]. Exercise has been shown to support the growth and branching of dendrites, the structures on neurons that receive inputs from another neuron, which is thought to underlie learning and memory processes, as well as to increase the production of new neurons in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for learning and memory [13-15].

Exercise may also promote neuroprotection, the ability of the brain to resist damage and injury [3]. Exercise has been shown to protect against the loss of neurons and synapses in animal models of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease [16, 17]. Additionally, inflammation is a major cause of neurodegeneration and cognitive loss; exercise may help minimize this.

Recent studies have started to uncover potential molecular pathways that could mediate the benefits of exercise on the brain, even though the precise mechanism underlying these effects is still not entirely understood. These pathways comprise growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, and neurotrophins, among other substances. Comprehending these basic mechanisms could facilitate the identification of novel targets for therapies intended to enhance cognitive performance and prevent or treat neurological conditions. Furthermore, the significance of individual variations in the way each person responds to exercise is being increasingly acknowledged. To maximize brain function, tailored exercise interventions may be required, as some people may respond better to exercise than others. Future studies should focus on determining the molecular mechanisms that underlie individual variations in how the body responds to exercise.

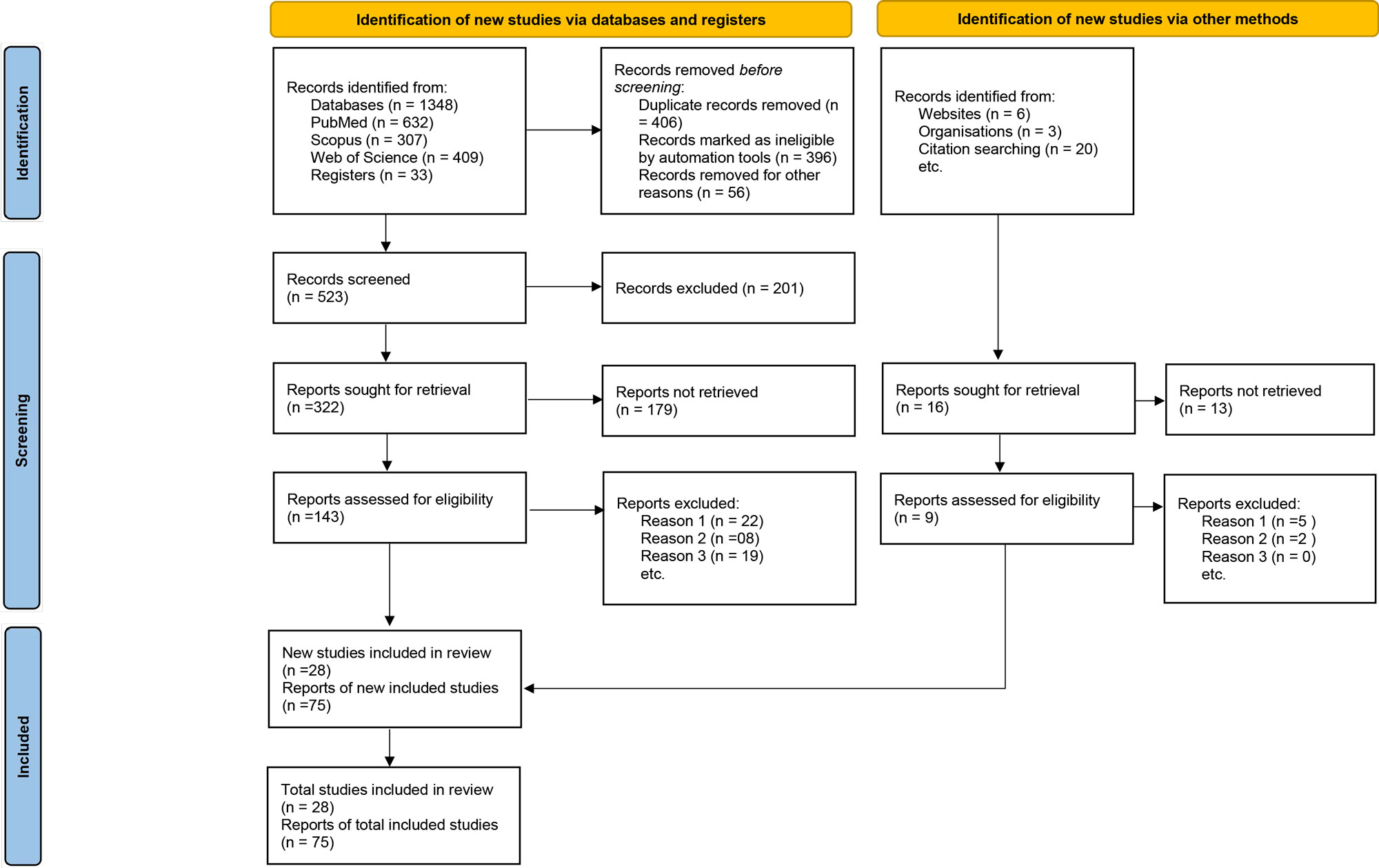

Using PRISMA criteria, a narrative review was conducted to thoroughly evaluate the positive effects of exercise on brain function and its implications for the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders (Figure 1).

Search strategy

We conducted a thorough search of electronic databases, which included PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, to find pertinent publications published between 2000 and 8th January 2023. phrases like "brain function," "exercise," "neurological disorders," "synaptic plasticity," "neurotrophic factors," and associated phrases were utilized.

Inclusion criteria

Studies on the impact of exercise on brain function and neurological diseases. Research papers that are published in journals with peer review. Research presents molecular perspectives on the modifications in brain function brought about by exercise. Papers composed in the English language.

Exclusion criteria

Reviews, opinion pieces, and non-research publications.

Studies that lack adequate mechanistic or molecular details.

Full-text versions of the articles are not accessible.

Study selection

The title and abstract are reviewed independently by two reviewers to ensure relevancy. Final inclusion was determined by evaluating full-text articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Using a standardized form, data were gathered on research parameters, participant demographics, exercise interventions, detected molecular changes, neurological outcomes, and pertinent findings.

Quality assessment

By using the proper tools, the methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated, considering variables including research design, methodology, and bias.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was carried out to provide an overview of the molecular pathways that have been found to underlie the effects of exercise on neurological diseases and brain function. The results were arranged into logical themes.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews, which included searches of databases, registers, and other sources.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews, which included searches of databases, registers, and other sources.

It has been discovered that exercise has beneficial impacts on the structure of the brain, including modifications to neuronal connections, gray matter density, and brain volume [18]. The hippocampus, a major brain area involved in memory and learning, has been demonstrated to increase in volume with exercise [19, 20]. A study by Erickson et al. (2011) found that older persons who engaged in a year-long program of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise had higher hippocampus volumes than the control group [21]. Similar results from animal studies have been observed that Exercise has been shown to improve the production of new neurons in the hippocampus [22].

Exercise may also have an impact on other brain regions, such as the basal ganglia, which control movement, and the prefrontal cortex, which is related to executive function. Prefrontal brain volume was higher in older persons who completed a six-month aerobic exercise program than in the control group, according to a study by Colcombe et al. (2006) [23]. Additionally, it has been discovered that exercise increases the density of gray matter in specific brain regions, including the anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal cortex [24, 25]. This rise in gray matter density could be a reflection of enhanced information processing and brain connections in these areas [26, 27].

Exercise has been shown to improve brain function and cognition in addition to structural alterations. For instance, a single session of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise enhanced preadolescent children's cognitive control and information processing, according to a study by Hillman et al. (2008) [28]. Adult working memory, executive function, and attention in both children and adults have all been demonstrated to be enhanced by exercise.

Exercise appears to have a variety of beneficial impacts on brain structure and function overall, including increases in brain capacity, gray matter density, and neural connections. Exercise's positive benefits on cognition and its ability to prevent age-related cognitive decline and neurological illnesses may be explained by these changes.

Effects of exercise on brain function

Studies have indicated that physical activity has a variety of advantageous impacts on mental and emotional functions, in addition to physiological alterations in the brain [29].

It has been demonstrated that exercise elevates the synthesis of neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, which play a role in mood, motivation, and emotional stability [30, 31]. It is well known and has been thoroughly researched how dopamine receptors affect the excitability of membrane potentials in striatal neurons [32, 33]. Through a complex process, D1 and D2 receptors modulate motor activities by influencing the excitatory transmission between post-synaptic striatal GABAergic neurons and presynaptic cortical glutamatergic neurons [33]. This complex interaction is essential in determining motor function and coordination. Extensive research on rodents has yielded important insights into the brain's response to sustained exercise. Numerous levels of modifications, including neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and cellular/molecular ones, were identified by these studies [34, 35]. Animal studies investigating the impact of exercise on the brain have shown structural modifications at the molecular (changes in neurotransmission, elevated neurotrophic factors) and cellular (neurogenesis, gliogenesis, synaptogenesis, angiogenesis) levels [36]. Behavioral tasks, particularly spatial tasks, have been used to assess functional activity and aid the study of spatial cognitive skills [32]. These studies offer helpful information about the positive effects of exercise on cognition.

Another study discovered that daily exercise could enhance serotonin availability by increasing the density of serotonin transporters in the brain [37]. The ability to decrease adenylyl cyclase activity is the primary characteristic shared by all six subtypes of the 5-HT1 receptor family (5-HT1A–F), which are members of the Gi-coupled receptor class. The 5-HT1A receptors are highly expressed in limbic areas, with the hippocampus being one of the most prominent postsynaptic receptor locations. They are also expressed as autoreceptors in the somatodendritic regions of the raphe nuclei [38]. These unique distribution patterns show their importance in a variety of cognitive and affective functions by underscoring their critical role in regulating serotonin signaling and neurotransmission. The principal molecular pathways through which exercise influences brain function, including neurotrophin signaling, mitochondrial biogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and inflammatory modulation, are summarized in Table 1.

Additionally, it has been discovered that exercise increases cerebral blood flow [39]. Sustaining normal brain function and vital metabolic processes depends on a constant and regular blood supply to the brain [40]. By improving the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to the brain cells, this enhanced blood flow may improve brain function. Furthermore, exercise can promote the development of new capillaries and blood vessels in the brain, which enhances the transport of nutrients and blood flow [41-43]. Previous research suggests that short-term exercise appears to have no appreciable effect on cerebral blood flow (CBF) or the blood vessels' capacity to adapt to variations in blood flow inside and outside of the brain [44]. Young people exhibited this finding, indicating that CBF is rapidly and reliably modulated following acute exercise sessions. Studies on animals have demonstrated that in rats with bilateral common carotid artery embolism, exercise increases the number of neurons in the hippocampus. Furthermore, it was shown that exercise slowed down the deterioration of cognitive function by promoting neurogenesis, the creation of new neurons, and increasing the expression of BDNF, a protein critical to the health and functionality of brain cells [44].

Exercise also influences the amounts of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the development and survival of neurons, which is another way that exercise can enhance brain function [45]. An increase in brain BDNF levels promotes synaptic plasticity, protects against neurodegenerative diseases, and improves learning and memory. [46, 47]. Strong evidence from recent studies suggests that regular, prolonged bouts of aerobic exercise can cause temporal increases in BDNF levels that were initially induced by acute exercise to proceed even further. This shows that aerobic exercise and the upregulation of BDNF are positively correlated, and this could have important effects on cognitive and brain health [48]. The primary player in the body's stress response is cortisol, a hormone released in reaction to a variety of stimuli, including psychological stress, worry, and terror. Stress also affects brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) concurrently. Increased stress has been associated with changes in BDNF mRNA, which in turn causes a decrease in BDNF expression. The complex relationship between BDNF and cortisol offers important insights into the neurobiological processes that underlie the impacts of stress on the brain and its possible impacts on brain health and cognitive function [49]. Zheng and colleagues observed a significant inverse relationship between cortisol and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [50]. Working memory can be understood as the cognitive domain that calls for conscious attention and mental effort, as proposed by Baddeley. Temporary information is actively stored, altered, and processed in this functional space, and it is essential to a variety of cognitive tasks and problem-solving activities [51]. According to Gathercole and Alloway, a person's capacity for working memory and their learning capacity are significantly and intricately related [52].

Cognitive benefits of exercise

Studies indicate that the effects of exercise on cognition may be due to modifications in brain structure and function caused by exercise [53]. The nervous system's ability to adapt and alter in response to events and learning is known as neuroplasticity. This amazing property allows the brain to rewire itself and create new connections, which affects how the brain functions and behaves [54]. Because of this, physical activity is shown to be a very beneficial environmental component that enhances and supports neuroplasticity, which in turn favorably affects the brain's ability to alter and restructure itself in response to experiences and learning.

Exercise has been proven in numerous studies to increase the volume of the hippocampus, a part of the brain essential for learning and memory, which may help to explain why exercise can enhance memory function [23, 55]. Exercise has been shown to have positive effects on cognitive performance at every stage of life, from early childhood to old age. Numerous studies have repeatedly demonstrated how exercise improves a range of cognitive functions, promoting brain health and cognitive capacities across the lifetime [56]. The variation noted amongst studies can potentially be linked to distinct factors that attenuate the effects of exercise on cognition. Genetic variations, such as the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele and the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met single-nucleotide polymorphism, can modulate the relationship between exercise and brain health. Genetic influences are among the factors that significantly influence this relationship. Exercise response and its effects on brain function and cognitive ability can be influenced by these hereditary factors [57, 58]. Strong evidence that increased physical activity is substantially associated with a lower incidence of cognitive decline and dementia was found through a meta-analytic assessment of 21 longitudinal studies including 89,205 persons 40 years of age and older [59]. An additional important meta-analysis including 15 prospective trials, showed that regular physical activity considerably decreased the chance of cognitive decline in participants by 38% [60]. Furthermore, there is strong evidence to support the idea that mind-body workouts can improve older persons' cognitive function. In an extensive meta-analysis carried out by Wu et al. [61], after taking part in 32 randomized controlled trials, older persons with and without cognitive impairment showed exceptional improvements in their learning, verbal fluency, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and global cognition. Zhang et al. conducted an extensive meta-analysis that included 11 randomized controlled trials [62], regardless of the presence of cognitive impairment, mind-body exercise has been shown to have substantial benefits on a range of adult cognitive functions. Notably, benefits were seen in language, learning, memory, executive function, and global cognition.

Exercise can also promote cerebral vascular function, which increases blood flow and oxygen supply to the brain, hence promoting neuronal activity and cognitive performance [63]. Exercise also lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all of which have a detrimental effect on brain function [64]. Risk factors for dementia and cognitive impairment include hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and hyperinsulinemia. These conditions also increase the risk of cerebrovascular disease and cardiovascular disease. These risk factors compound to degrade brain health, highlighting the need to manage and address vascular health to potentially reduce the risk of dementia and cognitive decline [65]. Researchers found that rising blood pressure and higher fasting blood glucose levels were linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in an extended observational trial that lasted 25 years and involved 3,381 participants [66]. Numerous studies have conclusively demonstrated the positive effects of exercise on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health [67, 68]. A noteworthy correlation was found between physical fitness, cerebrovascular regulation, and cognitive performance by Brown et al. in a cross-sectional study involving forty-two healthy older women [68], and by performing a mediational analysis within their randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 57 older persons, Smiley-Oyen and her team provided more data refuting the cardiovascular fitness hypothesis. The findings demonstrated that those who participated in aerobic exercise showed gains in executive function [69].

|

Table 1. Molecular mechanisms of exercise on brain function. |

||

|

Items |

Mechanism |

Principal contributors and outcomes |

|

Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise on Brain Function |

Neurotrophins and growth factors |

Synaptic plasticity and neuronal development are enhanced by BDNF release. |

|

Preserves neurodegenerative damage and enhances cognitive function. |

||

|

Mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative stress |

Promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, which increases the production of energy. |

|

|

Lowers oxidative stress by elevating antioxidant enzyme levels. |

||

|

Synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis |

Exercise promotes neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. |

|

|

Essential for memory, learning, and preventing neurodegeneration. |

||

Increased synthesis and release of neurotrophins and growth factors is one of the primary methods that exercise supports brain function [70]. In the brain, these proteins are essential for the growth, repair, and survival of neurons. Specifically, the beneficial effects of exercise on brain function have been linked to brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [71]. BDNF enhances synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis in addition to promoting the growth and survival of neurons [72]. According to multiple studies, Exercise boosts levels of BDNF in the brain, which has been linked to better cognitive performance and defense against neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's [73].

Mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative stress

The enhancement of mitochondrial biogenesis and the mitigation of oxidative stress are two additional significant ways that exercise improves brain function [74]. The powerhouses of the cell, mitochondria, are essential for the synthesis of energy. They are also crucial for preserving the homeostasis of cells and guarding against oxidative damage [75]. It has been demonstrated that exercise increases mitochondrial biogenesis, which enhances cellular function and increases energy output. Exercise may decrease oxidative stress by lowering the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and raising the production of antioxidant enzymes [76].

Synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that exercise promotes neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, two critical processes for brain health [77]. Neurogenesis is the process through which new neurons are formed in the brain, whereas synaptic plasticity is the capacity of neurons to change their connections in response to experience [78]. Both of these processes are vital for memory and learning, and neurological conditions like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's frequently affect them. Exercise has been demonstrated to increase neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, which improves cognitive function and guards against neurodegenerative disorders [79].

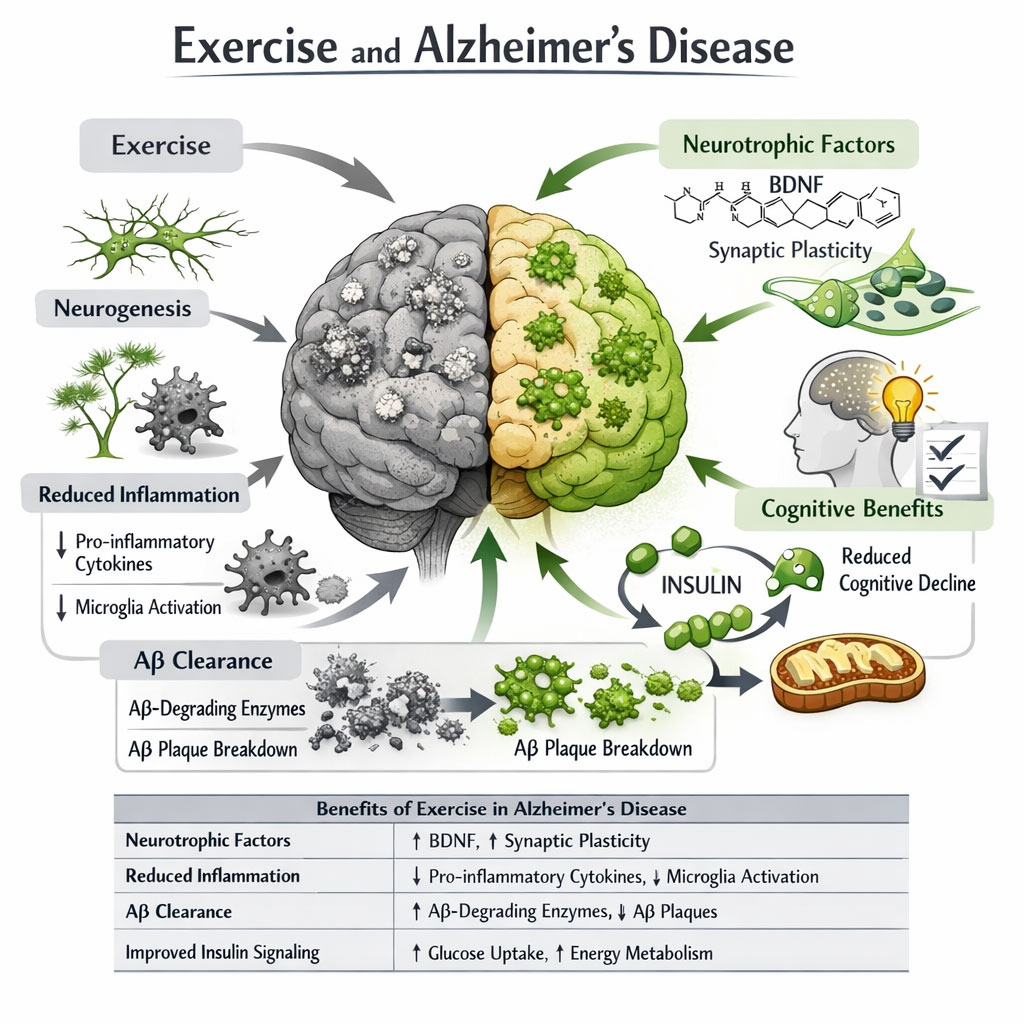

1. Neurotrophic factors. Frequent physical exercise stimulates the release of neurotrophic factors, specifically brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [80]. BDNF promotes neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal survival [81]. It promotes the growth of new synapses, which enhances cognitive function and could slow down cognitive aging [82].

2. Inflammation and oxidative stress. Exercise reduces inflammation by changing cytokine profiles and triggering immune cells, such as microglia [83]. By doing this, neuroinflammation is reduced, which minimizes the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's [84]. Exercise additionally strengthens the body's natural antioxidant defenses, preventing oxidative stress from damaging neurons [85].

3. Aβ Clearance: The hallmark of Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, is eliminated by exercise [86]. It increases cerebral blood flow and upregulates proteolytic enzymes that break down Aβ, making it easier for the brain to eliminate Aβ [87].

Insulin signalling and glucose metabolism. Exercise improves glucose utilization and insulin sensitivity [88]. Exercise promotes neuronal function and indirectly supports brain energy metabolism by improving peripheral insulin resistance [89]. Further, insulin is also essential for maintaining proteostasis. It influences the excretion of amyloid β peptide and the phosphorylation of tau, two important markers in Alzheimer's disease [90].

4. Synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis. Exercise increases synaptic connections and stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis [91]. Important roles are played by BDNF and other growth factors in the maintenance of cognitive capacities [92]. The importance of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in cognition is being highlighted by an increasing number of studies from research on humans and animals. Additionally, there is a strong correlation between neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and age-related cognitive loss [93]. The major molecular pathways through which exercise influences Alzheimer’s disease pathology, including neurotrophic signaling, neuroinflammation, amyloid-β clearance, and metabolic regulation, are illustrated in Figure 2.

Parkinson's disease

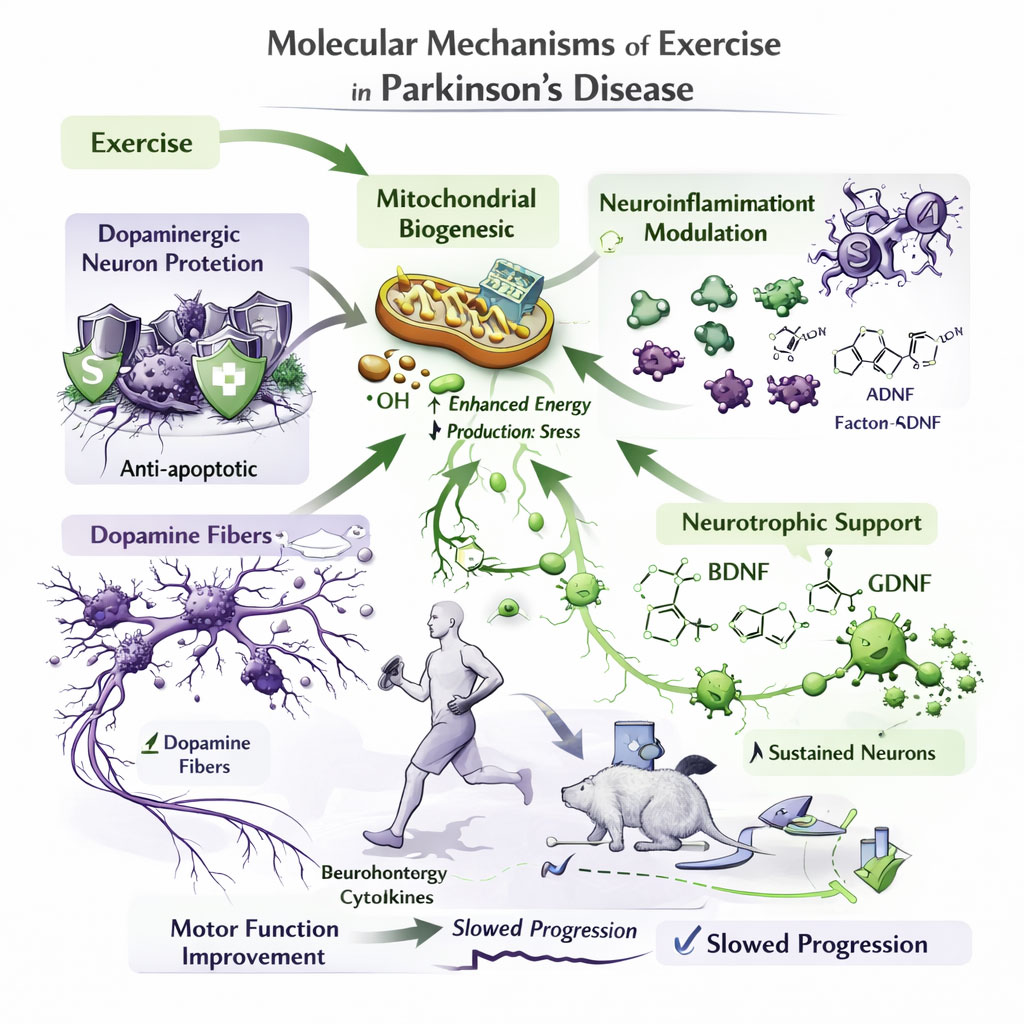

1. Dopaminergic neurons protection. By strengthening anti-apoptotic pathways, exercise may protect dopaminergic neurons and lessen the neuronal loss associated with Parkinson's disease [94].

2. Mitochondrial biogenesis. Exercise improves mitochondrial biogenesis and function, which is essential for generating energy and reducing oxidative stress, which is a key contributor to the development of Parkinson's disease [95, 96].

3. Neuroinflammation modulation. Frequent exercise influences cytokine profiles and microglial activation, which lowers neuroinflammation and may slow the progression of Parkinson's disease [97, 98].

4. Neurotrophic support. To maintain neuronal survival, function, and plasticity, exercise activates growth factors such as BDNF and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [99]. As Parkinson's disease progresses, there is an increasing amount of evidence that suggests a connection between diminishing BDNF levels and the condition [100]. Exercise-induced neuroprotective mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease, including dopaminergic neuron preservation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and neurotrophic support, are summarized in Figure 3.

Multiple sclerosis

1. Immune system regulation. Exercise can potentially reduce the autoimmune attack in multiple sclerosis by moderating the immune response and causing it to shift toward an anti-inflammatory state [101, 102].

2. Neuroprotection. Neuroprotective factors are released in response to exercise, protecting neurons from axonal injury and demyelination [103]. Contradictory results have been obtained from studies on the variations in BDNF levels in people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS). In general, BDNF levels tend to remain normal during times of remission while increasing during relapses [104].

3. Blood-brain barrier integrity. Exercise reduces immune cell infiltration and the possibility of a worsening of multiple sclerosis by maintaining the integrity of the blood-brain barrier [105, 106].

4. Functional compensation. Exercise increases the flexibility of brain networks, allowing the central nervous system to heal damaged areas [107]. In a healthy brain, an increase in neuronal activity can lead to new myelination and subsequent behavioral changes [108]. Using the natural ability of neuronal activity to direct myelination in conjunction with non-invasive techniques that can elicit neuronal activity could be a novel strategy for myelin repair in multiple sclerosis (MS) [109].

Depression and anxiety

1. Neurotransmitter regulation. Physical exercise affects neurotransmitter levels, elevating the release of serotonin and dopamine, which help to regulate mood and reduce feelings of anxiety and depression [110, 111].

2. Neuroplasticity and BDNF. Exercise promotes the synthesis of BDNF and neuroplasticity, which allows for neural adaptations to counteract the neuronal atrophy frequently seen in depression and anxiety [112-114].

3. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis modulation. Exercise lowers cortisol levels linked to mood disorders and chronic stress by normalizing the HPA axis [115, 116].

4. Endorphin release. Endorphins are natural painkillers that naturally occur and cause feelings of well-being and anxiety to decrease as one engages in physical exercise [117-119].

The disease-specific molecular effects of exercise across major neurological disorders are summarized in Table 2.

5. Implications for clinical populations. It's vital to take into account exercise's possible advantages for clinical populations given its many beneficial impacts on the brain. For those suffering from anxiety or depression as well as cognitive impairment, exercise may be a helpful solution.

6. Future directions. Although progress has been made, much remains unknown about how exercise impacts the brain. Future research should explore its mechanisms, benefits for clinical populations, and the optimal types and intensities for different neurological conditions and demographics, enabling tailored treatments that maximize benefits across all ages and health situations.

|

Table 2. Impacts of exercise on neurological disorders. |

||

|

Items |

Mechanism |

Impacts |

|

Impacts of exercise on Alzheimer's disease and dementia |

Neurotrophic factors |

Release of BDNF promotes synaptic plasticity and reduces cognitive deterioration. |

|

Inflammation and oxidative stress |

Workout strengthens antioxidant defenses and lowers neuroinflammation. |

|

|

Aβ clearance |

Enhances cerebral blood flow and encourages the removal of Aβ plaques. |

|

|

Insulin signalling and glucose metabolism |

Promotes insulin sensitivity and energy metabolism in the brain. |

|

|

Impacts of exercise on Parkinson's disease |

Dopaminergic neurons protection |

Reducing neuronal loss, exercise may protect dopaminergic neurons. |

|

Mitochondrial biogenesis |

Promotes mitochondrial performance and reduces oxidative stress. |

|

|

Neuroinflammation modulation |

Minimizes inflammation of the neurons, thus reducing Parkinson's. |

|

|

Neurotrophic support |

Promotes the growth factors that sustain the life and functionality of neurons. |

|

|

Impacts of exercise on multiple sclerosis |

Immune system regulation |

Exercise can potentially reduce the severity of an autoimmune attack by moderating the immunological response. |

|

Neuroprotection |

Activates neuroprotective factors, preventing demyelination of neurons. |

|

|

Blood-brain barrier integrity |

Reduction of immune cell infiltration and preservation of the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. |

|

|

Functional compensation |

Boosts the flexibility of brain networks to allow for functional correction. |

|

|

Impacts of exercise on depression and anxiety |

Neurotransmitter regulation |

Serotonin and dopamine are influenced by exercise, which helps regulate mood. |

|

Neuroplasticity and BDNF |

Reduces brain atrophy by increasing neuroplasticity and BDNF synthesis. |

|

|

HPA axis modulation |

Reduces cortisol levels linked to long-term stress by aiding in the HPA axis' normalization. |

|

|

Endorphin release |

Causes the release of endorphins, which elevate mood and decrease anxiety. |

|

Figure 2. Exercise modulates neurotrophic signaling, neuroinflammation, amyloid-β clearance, and metabolic pathways to reduce cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 2. Exercise modulates neurotrophic signaling, neuroinflammation, amyloid-β clearance, and metabolic pathways to reduce cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 3. Exercise promotes dopaminergic neuron survival, mitochondrial function, and neurotrophic support, thereby slowing disease progression and improving motor function in Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 3. Exercise promotes dopaminergic neuron survival, mitochondrial function, and neurotrophic support, thereby slowing disease progression and improving motor function in Parkinson’s disease.

As we conclude the present study, it is clear that exercise, with its complex chemical processes, is essential for maintaining brain function and has potential as a comprehensive strategy for treating and preventing neurological conditions. Future studies should focus more on specifically designed exercise programs for diverse neurological disorders to ensure that the benefits are maximized across a range of demographics and health situations. This review adds to the expanding body of research demonstrating that exercise plays a vital role in maintaining brain health and managing neurological disorders.

No applicable.

Ethics approval

No applicable.

Data availability

This narrative review is based on previously published studies and publicly available data. No new datasets were generated or analyzed for the current review.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contribution

Syed Muhammad Essa, Conceptualization, manuscript drafting, and overall supervision; Amanullah Kakar, Data collection and analysis; Noor Ahmed Khosa, Literature review and methodology support; Ismaiel A. Ibrahim, Statistical analysis and interpretation; Milica Jovanovic, Experimental design and validation; Maria Louise McLaughlin, Writing, review, and editing; Muhammad Ibrahim, Data curation and visualization; Karolina Riddle, Project administration and technical support.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

- Soga K, Higuchi A, Tomita N, Kobayashi K, Kataoka H, Imankulova A, Salazar C, Thyreau B, Nakamura S, Tsushita Y: Beneficial Effects of a 26-Week Exercise Intervention Using IoT Devices on Cognitive Function and Health Indicators. Int J Sports Med 2025, 7(2): 238-249.

- Zheng J, Luo W, Kong C, Xie W, Chen X, Qiu J, Wang K, Wei H, Zhou Y: Impact of aerobic exercise on brain metabolism: Insights from spatial metabolomic analysis. Behav Brain Res 2025, 478: 115339.

- Tari AR, Walker TL, Huuha AM, Sando SB, Wisloff U: Neuroprotective mechanisms of exercise and the importance of fitness for healthy brain ageing. Lancet 2025, 405(10484): 1093-1118.

- Luo S, Shi L, Liu T, Jin Q: Aerobic exercise training improves learning and memory performance in hypoxic-exposed rats by activating the hippocampal PKA–CREB–BDNF signaling pathway. BMC Neurosci 2025, 26(1): 13.

- Tang J, Lu L, Yuan J, Feng L: Exercise-induced Activation of SIRT1/BDNF/mTORC1 Signaling Pathway: A Novel Mechanism to Reduce Neuroinflammation and Improve Post-stroke Depression. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2025, 53(2): 366-378.

- Liu R, Menhas R, Saqib ZA: Does physical activity influence health behavior, mental health, and psychological resilience under the moderating role of quality of life? Front Psychol 2024, 15: 1349880.

- Luthans F, Luthans K, Luthans B, Peterson S: Psychological, physical, and social capitals: A balanced approach for more effective human capital in today’s organizations and life. Organizational Dynamics 2024, 53(4): 101080.

- Hills AP, Jayasinghe S, Arena R, Byrne NM: Global status of cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity–Are we improving or getting worse? Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2024, 83: 16-22.

- Ben Ezzdine L, Dhahbi W, Dergaa I, Ceylan HI, Guelmami N, Ben Saad H, Chamari K, Stefanica V, El Omri A: Physical activity and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review of exercise interventions, cognitive training, and AI applications. Front Neurosci 2025, 19: 1502417.

- Latino F, Tafuri F: Physical Activity and Cognitive Functioning. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60(2): 216.

- Martín-Rodríguez A, Gostian-Ropotin LA, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Belando-Pedreño N, Simón JA, López-Mora C, Navarro-Jiménez E, Tornero-Aguilera JF, Clemente-Suárez VJ: Sporting mind: the interplay of physical activity and psychological health. Sports 2024, 12(1): 37.

- Hossain MN, Lee J, Choi H, Kwak Y-S, Kim J: The impact of exercise on depression: how moving makes your brain and body feel better. Phys Act Nutr 2024, 28(2): 43.

- Hua Z, Sun J: Investigating Morphological Changes of the Hippocampus After Prolonged Aerobic Exercise in Mice: Neural Function and Learning Capabilities. Int J Morphol 2024, 42(3): 614-622.

- Seçer MB: Exercise and neuroplasticity. The Science of Neurolearning from Neurobiology to Education 2024, p59-78.

- Balbim GM, Boa Sorte Silva NC, Ten Brinke L, Falck RS, Hortobagyi T, Granacher U, Erickson KI, Hernandez-Gamboa R, Liu-Ambrose T: Aerobic exercise training effects on hippocampal volume in healthy older individuals: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Geroscience 2024, 46(2): 2755-2764.

- Sadri I, Nikookheslat SD, Karimi P, Khani M, Nadimi S: Aerobic exercise training improves memory function through modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and synaptic proteins in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of type 2 diabetic rats. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2024, 23(1): 849-858.

- Li S, Li M, Li G, Li L, Yang X, Zuo Z, Zhang L, Hu X, He X: Physical Exercise Decreases Complement‐Mediated Synaptic Loss and Protects Against Cognitive Impairment by Inhibiting Microglial Tmem9‐ATP6V0D1 in Alzheimer's Disease. Aging Cell 2025, 24(5): e14496.

- Killgore WD, Olson EA, Weber M: Physical exercise habits correlate with gray matter volume of the hippocampus in healthy adult humans. Sci Rep 2013, 3(1): 3457.

- Spalding KL, Bergmann O, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Huttner HB, Bostrom E, Westerlund I, Vial C, Buchholz BA et al: Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell 2013, 153(6): 1219-1227.

- Trejo JL, Carro E, Torres-Aleman I: Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci 2001, 21(5): 1628-1634.

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Heo S, Alves H, White SM et al: Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108(7): 3017-3022.

- Cotman CW, Engesser-Cesar C: Exercise enhances and protects brain function. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2002, 30(2): 75-79.

- Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, Kim JS, Prakash R, McAuley E, Elavsky S, Marquez DX, Hu L, Kramer AF: Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006, 61(11): 1166-1170.

- Erickson KI, Leckie RL, Weinstein AM: Physical activity, fitness, and gray matter volume. Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35 Suppl 2: S20-28.

- Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Esteban-Cornejo I, Torres-Lopez LV, Aadland E, Chastin SF, Erickson KI, Catena A, Ortega FB: Associations of Objectively-Assessed Physical Activity and Sedentary Time with Hippocampal Gray Matter Volume in Children with Overweight/Obesity. J Clin Med 2020, 9(4): 1080.

- Brown B, Peiffer J, Martins R: Multiple effects of physical activity on molecular and cognitive signs of brain aging: can exercise slow neurodegeneration and delay Alzheimer’s disease? Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18(8): 864-874.

- Scherder E, Scherder R, Verburgh L, Konigs M, Blom M, Kramer AF, Eggermont L: Executive functions of sedentary elderly may benefit from walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014, 22(8): 782-791.

- Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF: Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008, 9(1): 58-65.

- Audiffren M: Acute exercise and psychological functions: A cognitive-energetic approach. In T McMorris, P Tomporowski, & M Audiffren (Eds), Wiley Blackwell (Exercise and cognitive function) 2009, p3-39.

- Shimojo G, Joseph B, Shah R, Consolim-Colombo FM, De Angelis K, Ulloa L: Exercise activates vagal induction of dopamine and attenuates systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 75: 181-191.

- Valim V, Natour J, Xiao Y, Pereira AF, Lopes BB, Pollak DF, Zandonade E, Russell IJ: Effects of physical exercise on serum levels of serotonin and its metabolite in fibromyalgia: a randomized pilot study. Rev Bras Reumatol 2013, 53(6): 538-541.

- Mandolesi L, Gelfo F, Serra L, Montuori S, Polverino A, Curcio G, Sorrentino G: Environmental Factors Promoting Neural Plasticity: Insights from Animal and Human Studies. Neural Plast 2017, 2017: 7219461.

- Calabresi P, Pisani A, Centonze D, Bernardi G: Role of dopamine receptors in the short- and long-term regulation of corticostriatal transmission. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi 1997, 17(2): 101-104.

- Gligoroska JP, Manchevska S: The effect of physical activity on cognition–physiological mechanisms. Materia Socio-medica 2012, 24(3): 198.

- Dishman R, Berthoud H, Booth F, Cotman C, Edgerton V, Fleshner M, Gandevia S, Gomez-Pinilla F, Greenwood B, Hillman C: Neurobiology of Exercise. In., vol. 14 (3): Obesity; 2006: 345-356.

- Gelfo F, Mandolesi L, Serra L, Sorrentino G, Caltagirone C: The Neuroprotective Effects of Experience on Cognitive Functions: Evidence from Animal Studies on the Neurobiological Bases of Brain Reserve. Neuroscience 2018, 370: 218-235.

- Chennaoui M, Grimaldi B, Fillion M, Bonnin A, Drogou C, Fillion G, Guezennec C: Effects of physical training on functional activity of 5-HT 1B receptors in rat central nervous system: role of 5-HT-moduline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2000, 361(6): 600-604.

- Hoyer D, Hannon JP, Martin GR: Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2002, 71(4): 533-554.

- Querido JS, Sheel AW: Regulation of cerebral blood flow during exercise. Sports Med 2007, 37(9): 765-782.

- Liu J, Min L, Liu R, Zhang X, Wu M, Di Q, Ma XJSR: The effect of exercise on cerebral blood flow and executive function among young adults: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2023, 13(1): 8269.

- Finsterwald C, Magistretti PJ, Lengacher S: Astrocytes: New Targets for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Pharm Des 2015, 21(25): 3570-3581.

- Bélanger M, Allaman I, Magistretti PJJCm: Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab 2011, 14(6): 724-738.

- Guiney H, Lucas SJ, Cotter JD, Machado L: Evidence cerebral blood-flow regulation mediates exercise–cognition links in healthy young adults. Neuropsychology 2015, 29(1): 1-9.

- Steventon JJ, Hansen AB, Whittaker JR, Wildfong KW, Nowak-Flück D, Tymko MM, Murphy K, Ainslie PN: Cerebrovascular function in the large arteries is maintained following moderate intensity exercise. Front Physiol 2018, 9: 1657.

- de Melo Coelho FG, Gobbi S, Andreatto CAA, Corazza DI, Pedroso RV, Santos-Galduróz RF: Physical exercise modulates peripheral levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF): a systematic review of experimental studies in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013, 56(1): 10-15.

- Zoladz JA, Pilc A, Majerczak J, Grandys M, Zapart-Bukowska J, Duda K: Endurance training increases plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration in young healthy men. J Physiol Pharmacol 2008, 59 Suppl 7(Suppl 7): 119-132.

- Farmer J, Zhao X, Van Praag H, Wodtke K, Gage F, Christie B: Effects of voluntary exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male Sprague–Dawley rats in vivo. Neuroscience 2004, 124(1): 71-79.

- Griffin EW, Mullally S, Foley C, Warmington SA, O'Mara SM, Kelly AM: Aerobic exercise improves hippocampal function and increases BDNF in the serum of young adult males. Physiol Behav 2011, 104(5): 934-941.

- Russo-Neustadt A, Ha T, Ramirez R, Kesslak JPJBbr: Physical activity–antidepressant treatment combination: impact on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and behavior in an animal model. Behav Brain Res 2001, 120(1): 87-95.

- Ke Z, Yip SP, Li L, Zheng XX, Tong KY: The effects of voluntary, involuntary, and forced exercises on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and motor function recovery: a rat brain ischemia model. PLoS One 2011, 6(2): e16643.

- Baddeley A: The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends Cogn Sci 2000, 4(11): 417-423.

- Gathercole S, Alloway TP: Working memory and learning: A practical guide for teachers. Sage, 2008.

- Weinberg RS, Gould D: Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Human kinetics, 2023.

- Bavelier D, Neville HJJNRN: Cross-modal plasticity: where and how? Nat Rev Neurosci 2002, 3(6): 443-452.

- Chaddock-Heyman L, Erickson KI, Holtrop JL, Voss MW, Pontifex MB, Raine LB, Hillman CH, Kramer AF: Aerobic fitness is associated with greater white matter integrity in children. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8: 584.

- Hötting K, Röder B: Beneficial effects of physical exercise on neuroplasticity and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013, 37(9): 2243-2257.

- Brown BM, Bourgeat P, Peiffer JJ, Burnham S, Laws SM, Rainey-Smith SR, Bartrés-Faz D, Villemagne VL, Taddei K, Rembach A: Influence of BDNF Val66Met on the relationship between physical activity and brain volume. Neurology 2014, 83(15): 1345-1352.

- Brown BM, Castalanelli N, Rainey-Smith SR, Doecke J, Weinborn M, Sohrabi HR, Laws SM, Martins RN, Peiffer JJ: Influence of BDNF Val66Met on the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and memory in cognitively normal older adults. Behav Brain Res 2019, 362: 103-108.

- Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JLJBph: Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2014, 14: 510.

- Sofi F, Valecchi D, Bacci D, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Macchi CJJoim: Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta‐analysis of prospective studies. J Intern Med 2011, 269(1): 107-117.

- Wu C, Yi Q, Zheng X, Cui S, Chen B, Lu L, Tang C: Effects of mind‐body exercises on cognitive function in older adults: A meta‐analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019, 67(4): 749-758.

- Zhang Y, Li C, Zou L, Liu X, Song W: The Effects of Mind-Body Exercise on Cognitive Performance in Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15(12): 2791.

- Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Moore KA: Physical fitness and cognitive functioning in aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1994, 22(1): 195-220.

- Ainslie PN, Cotter JD, George KP, Lucas S, Murrell C, Shave R, Thomas KN, Williams MJ, Atkinson G: Elevation in cerebral blood flow velocity with aerobic fitness throughout healthy human ageing. J Physiol 2008, 586(16): 4005-4010.

- TUTOR I, TUTOR I: Vascular risk factors in Alzheimer’s disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: population data from the Zabùt Aging Project. PhD thesis of Palermo University 2017.

- Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Pletcher MJ, Hoang TD, Launer LJ, Whitmer RA, Coker LH, Sidney S: Early adult to midlife cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive function. Circulation 2014, 129(15): 1560-1567.

- Lin X, Zhang X, Guo J, Roberts CK, McKenzie S, Wu WC, Liu S, Song Y: Effects of exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2015, 4(7): e002014.

- Brown AD, McMorris CA, Longman RS, Leigh R, Hill MD, Friedenreich CM, Poulin MJ: Effects of cardiorespiratory fitness and cerebral blood flow on cognitive outcomes in older women. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31(12): 2047-2057.

- Smiley-Oyen AL, Lowry KA, Francois SJ, Kohut ML, Ekkekakis P: Exercise, fitness, and neurocognitive function in older adults: the “selective improvement” and “cardiovascular fitness” hypotheses. Ann Behav Med 2008, 36(3): 280-291.

- Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C, Sanchis-Gomar FJJos, science h: Updated overview on interplay between physical exercise, neurotrophins, and cognitive function in humans. J Sport Health Sci 2020, 9(1): 74-81.

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW: A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Psychiatr Res 2015, 60: 56-64.

- Liu PZ, Nusslock R: Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF. Front Neurosci 2018, 12: 52.

- Murawska-Ciałowicz E, Wiatr M, Ciałowicz M, Gomes de Assis G, Borowicz W, Rocha-Rodrigues S, Paprocka-Borowicz M, Marques A: BDNF impact on biological markers of depression—role of physical exercise and training. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(14): 7553.

- Lee HC, Wei YH: Mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA maintenance of mammalian cells under oxidative stress. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2005, 37(4): 822-834.

- Ma T, Huang X, Zheng H, Huang G, Li W, Liu X, Liang J, Cao Y, Hu Y, Huang Y: SFRP2 Improves Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021: 9265016.

- Afolayan AJ, Eis A, Alexander M, Michalkiewicz T, Teng RJ, Lakshminrusimha S, Konduri GG: Decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and function contribute to impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative stress in fetal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016, 310(1): L40-49.

- Stuchlik A: Dynamic learning and memory, synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis: an update. Front Behav Neurosci 2014, 8: 106.

- Magee JC, Grienberger C: Synaptic Plasticity Forms and Functions. Annu Rev Neurosci 2020, 43: 95-117.

- D Skaper S, Facci L, Zusso M, Giusti P: Synaptic plasticity, dementia and Alzheimer disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2017, 16(3): 220-233.

- Huang T, Larsen K, Ried‐Larsen M, Møller N, Andersen LB: The effects of physical activity and exercise on brain‐derived neurotrophic factor in healthy humans: A review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014, 24(1): 1-10.

- Gomez‐Pinilla F, Vaynman S, Ying Z: Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor functions as a metabotrophin to mediate the effects of exercise on cognition. Eur J Neurosci 2008, 28(11): 2278-2287.

- Jeon YK, Ha CH: The effect of exercise intensity on brain derived neurotrophic factor and memory in adolescents. Environ Health Prev Med 2017, 22(1): 27.

- Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA: The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11(9): 607-615.

- Leri M, Vasarri M, Carnemolla F, Oriente F, Cabaro S, Stio M, Degl’Innocenti D, Stefani M, Bucciantini MJP: EVOO Polyphenols Exert Anti-Inflammatory Effects on the Microglia Cell through TREM2 Signaling Pathway. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16(7): 933.

- Lee WJJIn: IGF-I exerts an anti-inflammatory effect on skeletal muscle cells through down-regulation of TLR4 signaling. Immune Netw 2011, 11(4): 223-226.

- Lin J, Gao S, Wang T, Shen Y, Yang W, Li Y, Hu H: Ginsenoside Rb1 improves learning and memory ability through its anti-inflammatory effect in Aβ1-40 induced Alzheimer’s disease of rats. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11(5): 2955-2968.

- Xin S-H, Tan L, Cao X, Yu J-T, Tan LJNr: Clearance of amyloid beta and tau in Alzheimer’s disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Neurotox Res 2018, 34(3): 733-748.

- Keshel TE, Coker RH: Exercise Training and Insulin Resistance: A Current Review. J Obes Weight Loss Ther 2015, 5(Suppl 5): S5-003.

- Malin SK, Stewart NR, Ude AA, Alderman BL: Brain insulin resistance and cognitive function: influence of exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2022, 133(6): 1368-1380.

- Kim OY, Song J: The role of irisin in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Med 2018, 7(11): 407.

- Lev-Vachnish Y, Cadury S, Rotter-Maskowitz A, Feldman N, Roichman A, Illouz T, Varvak A, Nicola R, Madar R, Okun E: L-Lactate Promotes Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Front Neurosci 2019, 13: 403.

- Gao Y, Syed M, Zhao X: Mechanisms underlying the effect of voluntary running on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus 2023, 33(4): 373-390.

- Ma CL, Ma XT, Wang JJ, Liu H, Chen YF, Yang Y: Physical exercise induces hippocampal neurogenesis and prevents cognitive decline. Behav Brain Res 2017, 317: 332-339.

- Muñoz A, Corrêa CL, Lopez-Lopez A, Costa-Besada MA, Diaz-Ruiz C, Labandeira-Garcia JL: Physical exercise improves aging-related changes in angiotensin, IGF-1, SIRT1, SIRT3, and VEGF in the substantia nigra. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018, 73(12): 1594-1601.

- Yokokawa T, Kido K, Suga T, Isaka T, Hayashi T, Fujita S: Exercise‐induced mitochondrial biogenesis coincides with the expression of mitochondrial translation factors in murine skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep 2018, 6(20): e13893.

- Ferreira AFF, Binda KH, Singulani MP, Pereira CPM, Ferrari GD, Alberici LC, Real CC, Britto LR: Physical exercise protects against mitochondria alterations in the 6-hidroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav Brain Res 2020, 387: 112607.

- Chromiec PA, Urbas ZK, Jacko M, Kaczor JJ: The Proper Diet and Regular Physical Activity Slow Down the Development of Parkinson Disease. Aging Dis 2021, 12(7): 1605-1623.

- A McKenzie J, J Spielman L, B Pointer C, R Lowry J, Bajwa E, W Lee C, Klegeris AJCas: Neuroinflammation as a common mechanism associated with the modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Curr Aging Sci 2017, 10(3): 158-176.

- Almeida C, DeMaman A, Kusuda R, Cadetti F, Ravanelli MI, Queiroz AL, Sousa TA, Zanon S, Silveira LR, Lucas G: Exercise therapy normalizes BDNF upregulation and glial hyperactivity in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Pain 2015, 156(3): 504-513.

- Palasz E, Wysocka A, Gasiorowska A, Chalimoniuk M, Niewiadomski W, Niewiadomska G: BDNF as a promising therapeutic agent in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(3): 1170.

- Cerqueira É, Marinho DA, Neiva HP, Lourenço O: Inflammatory effects of high and moderate intensity exercise—a systematic review. Front Physiol 2020, 10: 1550.

- Faramarzi M, Banitalebi E, Raisi Z, Samieyan M, Saberi Z, Ghahfarrokhi MM, Negaresh R, Motl RWJC: Effect of combined exercise training on pentraxins and pro-inflammatory cytokines in people with multiple sclerosis as a function of disability status. Cytokine 2020, 134: 155196.

- Diechmann MD, Campbell E, Coulter E, Paul L, Dalgas U, Hvid LG: Effects of exercise training on neurotrophic factors and subsequent neuroprotection in persons with multiple sclerosis—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci 2021, 11(11): 1499.

- Riemenschneider M, Hvid LG, Ringgaard S, Nygaard MKE, Eskildsen SF, Gaemelke T, Magyari M, Jensen HB, Nielsen HH, Kant M et al: Investigating the potential disease-modifying and neuroprotective efficacy of exercise therapy early in the disease course of multiple sclerosis: The Early Multiple Sclerosis Exercise Study (EMSES). Mult Scler 2022, 28(10): 1620-1629.

- Shamsaei N, Abdi H, Moradi F: Physical training moderates blood-brain-barrier disruption and improves cognitive dysfunction related to transient brain ischemia in rats. Neurophysiology 2019, 51: 438-446.

- Lozinski BM, Yong VW: Exercise and the brain in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2022, 28(8): 1167-1172.

- Won J, Callow DD, Pena GS, Gogniat MA, Kommula Y, Arnold-Nedimala NA, Jordan LS, Smith JC: Evidence for exercise-related plasticity in functional and structural neural network connectivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 131: 923-940.

- Yeung MS, Djelloul M, Steiner E, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Possnert G, Brundin L, Frisén J: Oligodendrocyte generation dynamics in multiple sclerosis. Nature 2019, 566(7745): 538.

- Maas DA, Angulo MCJFiCN: Can enhancing neuronal activity improve myelin repair in multiple sclerosis? Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15: 645240.

- Arazi H, Dadvand SS, Suzuki KJBHK: Effects of exercise training on depression and anxiety with changing neurotransmitters in methamphetamine long term abusers: A narrative review. Biomedical Human Kinetics 2022, 14(1): 117-126.

- Maurus I, Hasan A, Roh A, Takahashi S, Rauchmann B, Keeser D, Malchow B, Schmitt A, Falkai P: Neurobiological effects of aerobic exercise, with a focus on patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019, 269(5): 499-515.

- Jemni M, Zaman R, Carrick FR, Clarke ND, Marina M, Bottoms L, Matharoo JS, Ramsbottom R, Hoffman N, Groves SJJFiP: Exercise improves depression through positive modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). A review based on 100 manuscripts over 20 years. Front Physiol 2023, 14: 1102526.

- Chakrapani S, Eskander N, De Los Santos LA, Omisore BA, Mostafa JA: Neuroplasticity and the Biological Role of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor in the Pathophysiology and Management of Depression. Cureus 2020, 12(11): e11396.

- Gökçe E, Güneş E, Nalcaci E: Effect of exercise on major depressive disorder and schizophrenia: a BDNF focused approach. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 2019, 56(4): 302.

- Anderson T, Berry NT, Wideman LJCOiE, Research M: Exercise and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis: a special focus on acute cortisol and growth hormone responses. Curr Opin Endoc Metab Res 2019, 9: 74-77.

- Chen L, Wang X, Zhang Y, Zhong H, Wang C, Gao P, Li B: Daidzein Alleviates Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Hyperactivity, Ameliorates Depression-Like Behavior, and Partly Rectifies Circulating Cytokine Imbalance in Two Rodent Models of Depression. Front Behav Neurosci 2021, 15: 671864.

- Ji J, McGinnis A, Ji R-R: Exercise and Diet in the Control of Inflammation and Pain. In: Neuroimmune Interactions in Pain: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. edn.: Springer 2023, p305-320.

- Jain A, Mishra A, Shakkarpude J, Lakhani P: Beta endorphins: the natural opioids. IJCS 2019, 7(3): 323-332.

- Blumenthal JA, Rozanski A: Exercise as a therapeutic modality for the prevention and treatment of depression. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2023, 77: 50-58.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Surgical & Experimental Pathology

ISSN 2977-5817 (Online)

Copyright © Asia Pac J Surg Exp & Pathol. This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

License.

Copyright © Asia Pac J Surg Exp & Pathol. This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript